This is part two of the write-up of my talk at ODSC Europe 2024 and ODSC West 2024.

In the last few years, the world of voice agents saw dramatic leaps forward in the state of the art of all its most basic components. Thanks mostly to OpenAI, bots are now able to understand human speech almost like a human would, they’re able to speak back with completely naturally sounding voices, and are able to hold a free conversation that feels extremely natural.

But building reliable and effective voice bots is far from a solved problem. These improved capabilities are raising the bar, and even users accustomed to the simpler capabilities of old bots now expect a whole new level of quality when it comes to interacting with them.

In Part 1 we’ve seen mostly the challenges related to building such bot: we discussed the basic structure of most voice bots today, their shortcomings and the main issues that you may face on your journey to improve the quality of the conversation.

In this post instead we will focus on the solutions that are available today and we are going to build our own voice bot using Pipecat, a recently released open-source library that makes building these bots a lot simpler.

Outline

Start from Part 1.

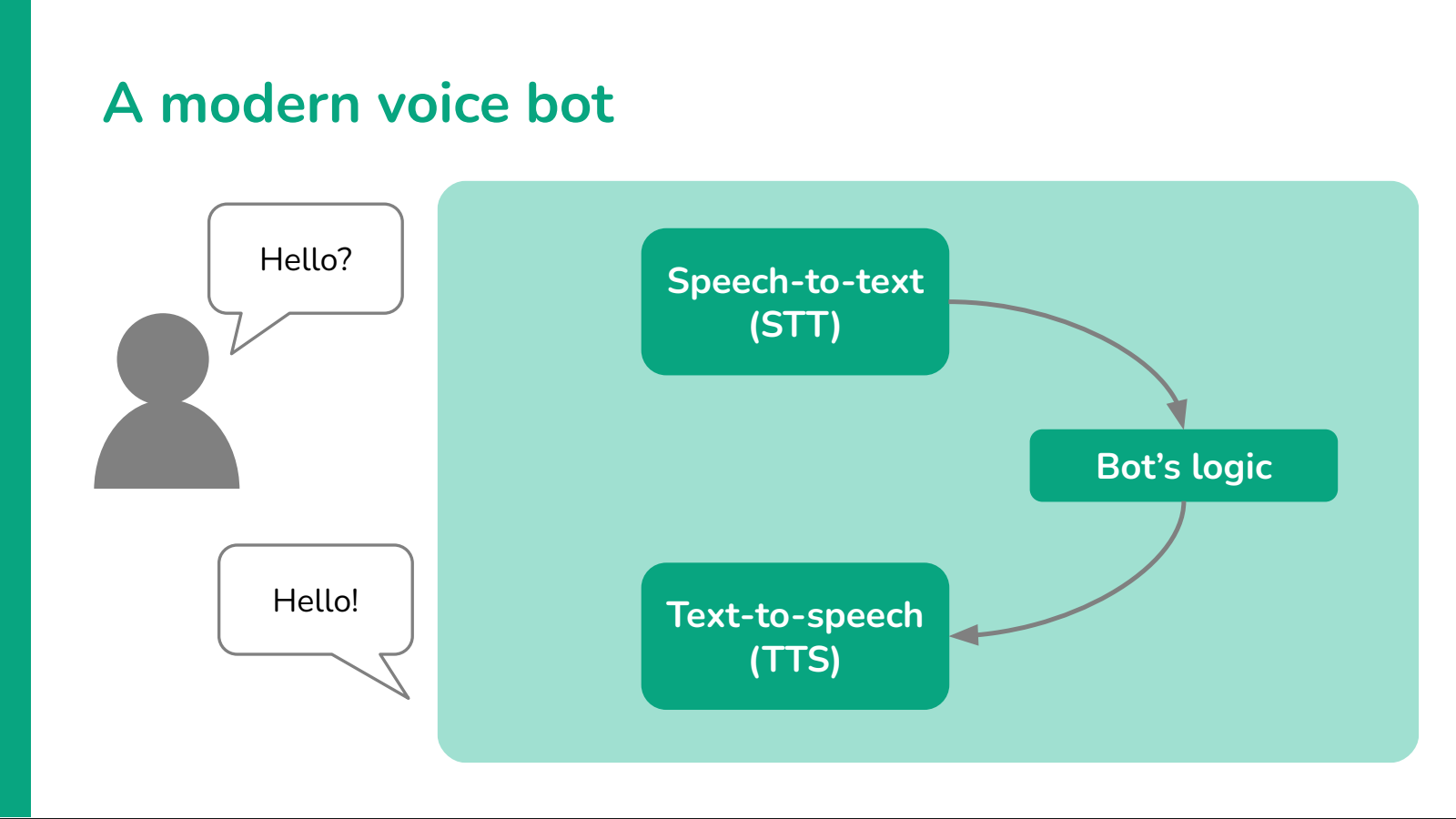

A modern voice bot

At this point we have a comprehensive view of the issues that we need to solve to create a reliable, usable and natural-sounding voice agents. How can we actually build one?

First of all, let’s take a look at the structure we defined earlier and see how we can improve on it.

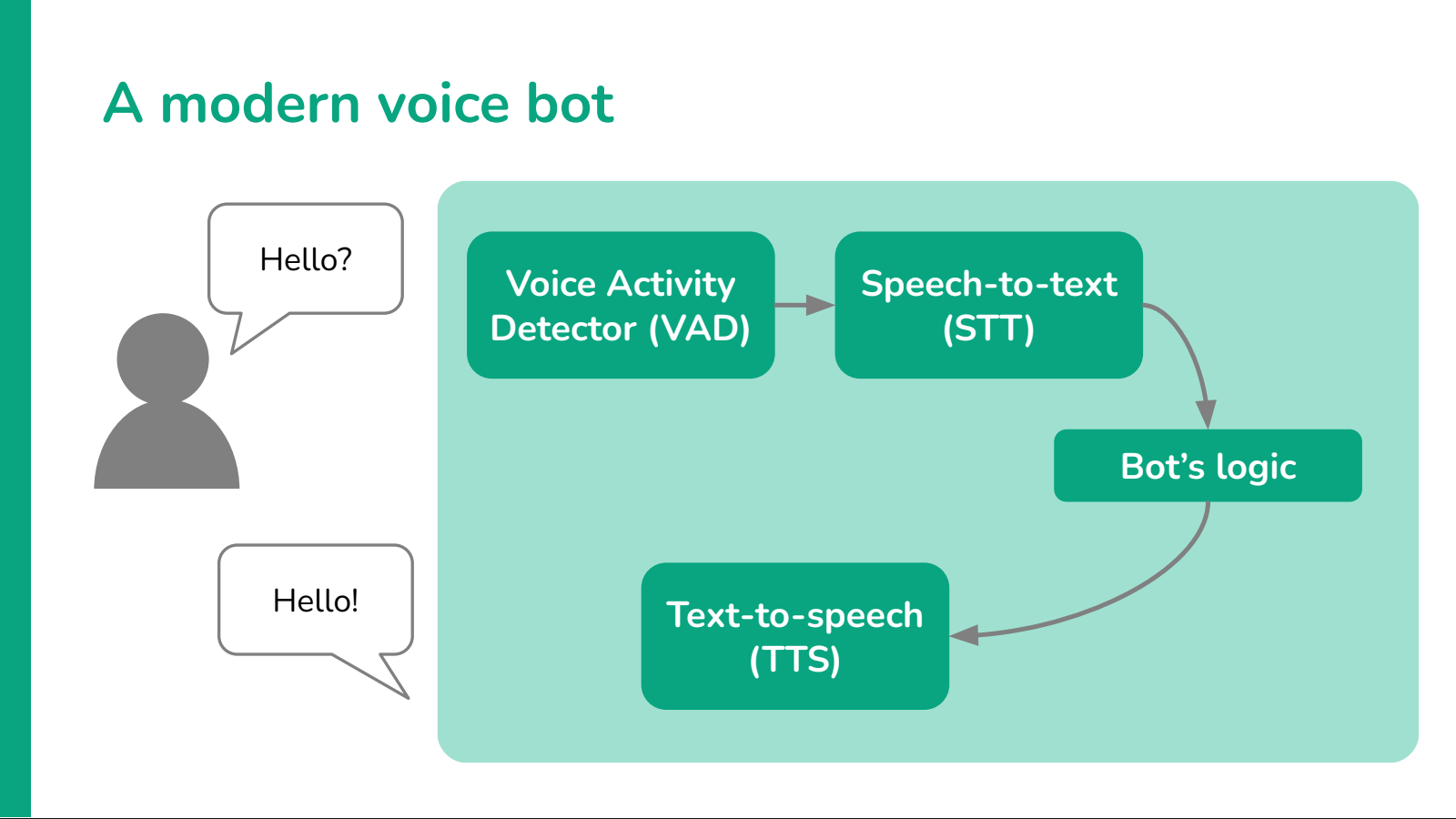

Voice Activity Detection (VAD)

One of the simplest improvements to this architecture is the addition of a robust Voice Activity Detection (VAD) model. VAD gives the bot the ability to hear interruptions from the user and react to them accordingly, helping to break the classic, rigid turn-based interactions of old-style bots.

However, on its own VAD models are not enough. To make a bot truly interruptible we also need the rest of the pipeline to be aware of the possibility of an interruption and be ready to handle it: speech-to-text models need to start transcribing and the text-to-speech component needs to stop speaking as soon as the VAD picks up speech.

The logic engine also needs to handle a half-spoken reply in a graceful way: it can’t just assume that the whole reply was spoken out, and neither it can drop the whole reply as it never started. Most LLMs can handle this scenario by altering the last message in their conversation history, but implementing this workflow in practice is often not straightorward, because you need to keep track of how much of the reply was heard by the user, and when exactly this interruption happened.

The quality of your VAD model matters a lot, as well as tuning its parameters appropriately. You don’t want the bot to interrupt itself at every ambient sound it detects, but you also want the interruption to happen promptly, with a few hundreds of milliseconds of delay. Some of the best and most used models out there are Silero’s VAD models, or alternatively Picovoice’s Cobra models.

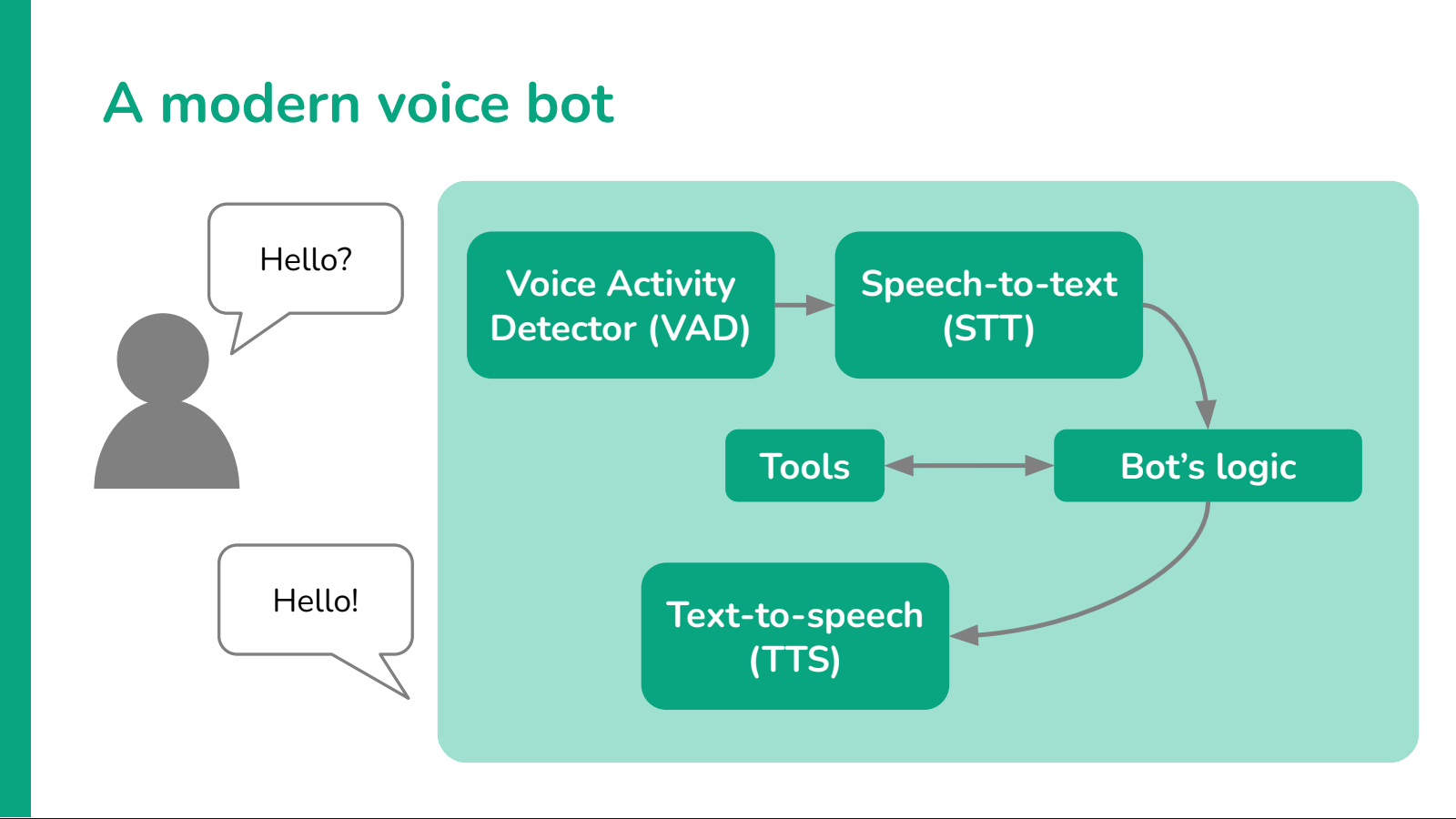

Tools

Tools are often a major component of you bot’s functionality. Modern and effective voice bots today are often able to take basic actions such as looking up data in a database or calling simple functions.

Function calling is a feature of most of today’s LLMs, so it’s often a low-hanging fruit in terms of improvements to your bot. Simple actions like looking up the current time, or searching a knowledge base before replying (a technique called Agentic RAG), may make a huge difference in terms of the quality of its responses.

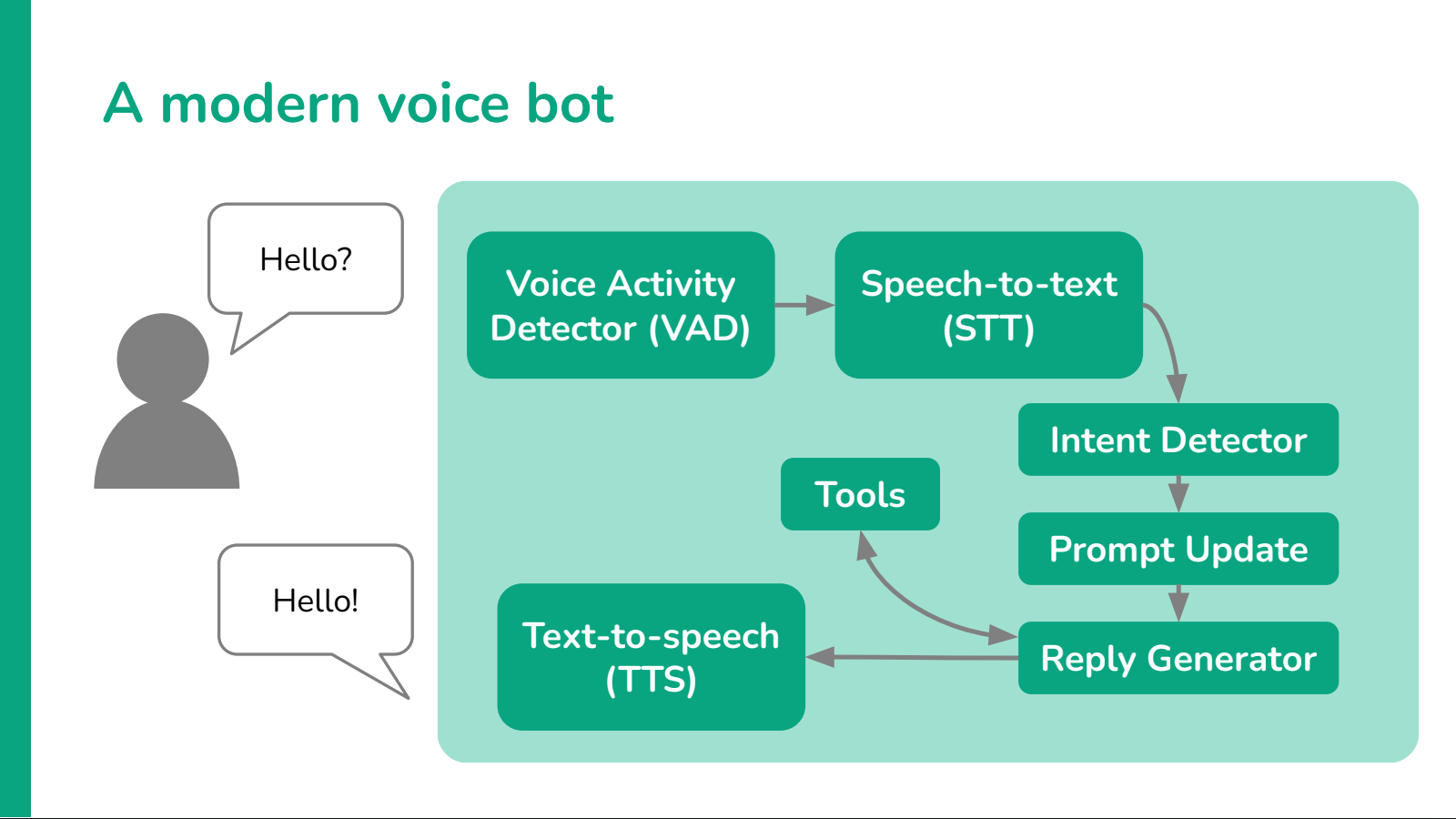

LLM-based intent detection

Despite the distinction we made earlier between tree-based, intent-based and LLM-based bots, often the logic of voice bots is implemented in a blend of more than one style. Intent-based bots may contain small decision trees, as well as LLM prompts. Often these approaches deliver the best results by taking the best of each to compensate for the weaknesss of the others.

One of the most effective approaches is to use intent detection to help control the flow of an LLM conversation. Let’s see how.

Suppose we’re building a general purpose customer support bot.

A bot like this needs to be able to handle a huge variety of requests: helping the user renew subscriptions, buy or return items, update them on the state of a shipping, telling the opening hours of the certified repair shop closer to their home, explaining the advantages of a promotion, and more.

If we decide to implement this chatbot based on intents, we risk that in many cases users won’t be able to find out how to achieve their goal, because many intent will look similar and there are many corner case requests that the original developers may not have foreseen.

However, if we decide to implement this chatbot with an LLM, it becomes really hard to check its replies and make sure that the bot is not lying, because the amount of instructions its system prompt will end up containing is huge. The bot may also perform actions that it is not supposed to, like letting users return an item they have no warranty on anymore.

There is an intermediate solution: first try to detect intent, then leverage the LLM.

Intent detection

Step one is detecting the intention of the user. This step can be done with an LLM by sending it a message such as this:

Given the following conversation, select the intent

of the user:

1: Return an item

2: Help to use the product

3: Apply for a subscription

4: Get information about official repair centers

5: Find the nearest retail center near them

6: Learn about current promotion campaigns

Conversation:

assistant: Hello! How can I help you today?

user: Hello, can you tell me if there's a repair shop for your product ABC open right now in Queens?

You can see that at this stage we don’t need to micromanage the model and we can stick to macro-categories safely. No need to specify “Find the opening hours of certified repair shops in New York”, bur rather “Find information on certified repair shops” in general will suffice.

This first steps narrows down drastically the scope of the conversation and, as a consequence, the amount of instructions that the LLM needs to handle to carry on the conversation effectively.

So the next step is to retrieve these instructions

Prompt update

Once we know what the user’s intention is, it’s time to build the real prompt that will give us a reply for the user.

With the general intent identified, we can equip the LLM strictly with the tools and information that it needs to proceed. If the user is asking about repair shops in their area, we can provide the LLM with a tool to search repair shops by zip code, a tool that would be useless if the user was asking about a shipment or a promotional campaign. Same for the background information: we don’t need to tell the LLM that “you’re a customer support bot”, but we can narrow down its personality and background knowledge to make it focus a lot more on the task at hand, which is to help the user locating a suitable repair shop. And so on.

This can be done by mapping each expected intent to a specific system prompt, pre-compiled to match the intent. At the prompt building stage we simply pick from our library of prompts and replace the system prompt with the one that we just selected.

For example, in our case the LLM selected intent n.4, “Get information about official repair centers”. This intent may correspond to a prompt like the following:

You’re a helpful assistant helping a user finding the best

repair center for them.

You can use the tool `find_repair_center` to get a list of

centers that match your query. Before calling the tool,

make sure to ask them for their zip code. If they asked about

a specific opening time, you can also use the `get_datetime`

tool to translate relative time (such as "now" or "tomorrow")

into a specific date and time (like 2024-01-24 10:24:32)

Don't forget about timezones. ...

Reply generation

With the new, narrower system prompt in place at the head of the conversation, we can finally prompt the LLM again to generate a reply for the user. The LLM, following the instructions of the updated prompt, has an easier time following its instructions (because they’re simpler and more focused) and generated better quality answers for both the users and the developers.

With a prompt like the above, the reply from the LLM is most likely going to be about the zipcode, something that normally an LLM would not attempt to ask for.

assistant: Hello! How can I help you today?

user: Hello, can you tell me if there's a repair shop for your product ABC open right now in Queens?

assistant: Sure, let me look it up! Can you please tell me your zipcode?

What about latency?

With all these additional back-and-forth with the LLM, it’s easy to find ourselves into a situation where latency gets out of hand. With only half a second of time to spare, making sure the system works as efficiently as possible is crucial.

With today’s models there are a few technical and non-technical ways to manage the latency of your bots and keep it under control.

Model colocation

Colocating models means that, instead of hosting each model on a different server or SaaS provider, you host all of them on the same machine or server rack, very close together.

Colocation can be helpful to reduce or remove entirely the overhead of network requests, which often is the largest source of latency in your bots. Colocation is very powerful for bringing latency down, however it’s not always feasible if you’re using proprietary models that don’t allow self-hosting.

Keep in mind also that colocation can backfire if your hardware is not suitable for the needs of the models you’re running. If you don’t have GPUs available, or they don’t fit all the models you need to colocate, your latency might increase dramatically.

I/O streaming

Modern LLMs and STT/TTS models are able to stream either their input or their output. The time it takes these models to generate the start of their output is often much faster than the time they take to generate the entire reply, so streaming the output of one into the input of the next will bring down the latency of the whole system by orders of magnitude.

Endpointing, for example, is the technical term for the ability of a speech to text model to detect the end of a sentence and send it over to an LLM while it listens for the rest of the user’s message. LLMs, while unable to take token-by-token inputs, can stream out their replies in this way. Text to speech then can detect dots and commas in the output stream to aggregate the tokens into sentences or phrases and start reading them out long before the last token is produced by the LLM.

This is exactly what frameworks like Pipecat enable for all their models, and it’s usually possible for all moderns LLMs.

Declaring the latency

If all technical solutions fails, one unconventional approach is to make the bot declare its own latency at the very start of the conversation. While it might sound silly, if a bot opens the chat saying I might be a bit slow, so be patient with me users are automatically more keen to wait longer for the bot’s response instead of pinging it continuously. While this does not make for the best user experience, being honest about your bot’s capabilities is always appreciated.

This technique, however, is not a band-aid for any sort of delay. Users won’t manage to talk to a bot if each reply takes more than one or two seconds to come back to them, regardless of how patient they might be.

Buying time

Last but not least, occasionally the bot might have a spike in latency due to the usage of a slow tool. When your bot knows that its reply is going to take longer than usual, it’s best, again, to warn the user by telling them what’s going on. Having the bot say something like Ok, let me look it up, it will take a few seconds is a huge user experience improvement you should not underestimate.

The code

Now that we’ve seen all the techniques that can make your bot effective, reliable and fast, it’s time to actually implement one!

One of the best frameworks out there to build open-source voice bots right now is Pipecat, a small library maintained by Daily.co.

Here you can find a commented Colab notebook to learn how Pipecat can help you build a very basic voice bots, how to implement the intent-detection system we’ve outlined above, and try such a bot yourself. Watch out: you’ll need a few API keys, but if you don’t have a specific one, often the Pipecat documentation can help you find a replacement component for any alternative model provider you may have access to.

Have fun!

The Pipecat bot in action (from my talk at ODSC West 2024, presenting this same notebook).