The concept of Agent is one of the vaguest out there in the post-ChatGPT landscape. The word has been used to identify systems that seem to have nothing in common with one another, from complex autonomous research systems down to a simple sequence of two predefined LLM calls. Even the distinction between Agents and techniques such as RAG and prompt engineering seems blurry at best.

Let’s try to shed some light on the topic by understanding just how much the term “AI Agent” covers and set some landmarks to better navigate the space.

Defining “Agent”

The problem starts with the definition of “agent”. For example, Wikipedia reports that a software agent is

a computer program that acts for a user or another program in a relationship of agency.

This definition is extremely high-level, to the point that it could be applied to systems ranging from ChatGPT to a thermostat. However, if we restrain our definition to “LLM-powered agents”, then it starts to mean something: an Agent is an LLM-powered application that is given some agency, which means that it can take actions to accomplish the goals set by its user. Here we see the difference between an agent and a simple chatbot, because a chatbot can only talk to a user. but don’t have the agency to take any action on their behalf. Instead, an Agent is a system you can effectively delegate tasks to.

In short, an LLM powered application can be called an Agent when

it can take decisions and choose to perform actions in order to achieve the goals set by the user.

Autonomous vs Conversational

On top of this definition there’s an additional distinction to take into account, normally brought up by the terms autonomous and conversational agents.

Autonomous Agents are applications that don’t use conversation as a tool to accomplish their goal. They can use several tools several times, but they won’t produce an answer for the user until their goal is accomplished in full. These agents normally interact with a single user, the one that set their goal, and the whole result of their operations might be a simple notification that the task is done. The fact that they can understand language is rather a feature that lets them receive the user’s task in natural language, understand it, and then to navigate the material they need to use (emails, webpages, etc).

An example of an autonomous agent is a virtual personal assistant: an app that can read through your emails and, for example, pays the bills for you when they’re due. This is a system that the user sets up with a few credentials and then works autonomously, without the user’s supervision, on the user’s own behalf, possibly without bothering them at all.

On the contrary, Conversational Agents use conversation as a tool, often their primary one. This doesn’t have to be a conversation with the person that set them off: it’s usually a conversation with another party, that may or may not be aware that they’re talking to an autonomous system. Naturally, they behave like agents only from the perspective of the user that assigned them the task, while in many cases they have very limited or no agency from the perspective of the users that holds the conversation with them.

An example of a conversational agent is a virtual salesman: an app that takes a list of potential clients and calls them one by one, trying to persuade them to buy. From the perspective of the clients receiving the call this bot is not an agent: it can perform no actions on their behalf, in fact it may not be able to perform actions at all other than talking to them. But from the perspective of the salesman the bots are agents, because they’re calling people for them, saving a lot of their time.

The distinction between these two categories is very blurry, and some systems may behave like both depending on the circumnstances. For example, an autonomous agent might become a conversational one if it’s configured to reschedule appointments for you by calling people, or to reply to your emails to automatically challenge parking fines, and so on. Alternatively, an LLM that asks you if it’s appropriate to use a tool before using it is behaving a bit like a conversational agent, because it’s using the chat to improve its odds of providing you a better result.

Degrees of agency

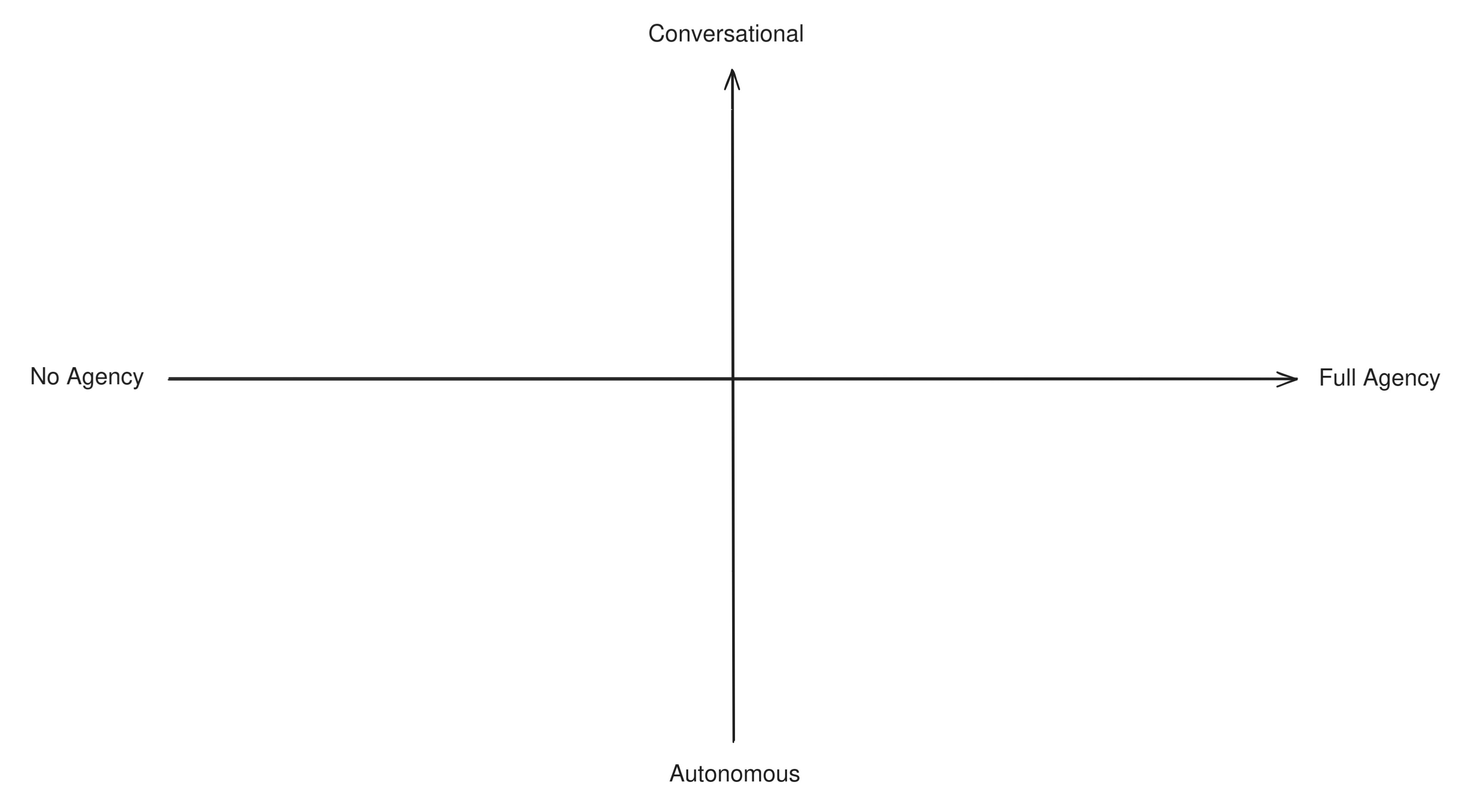

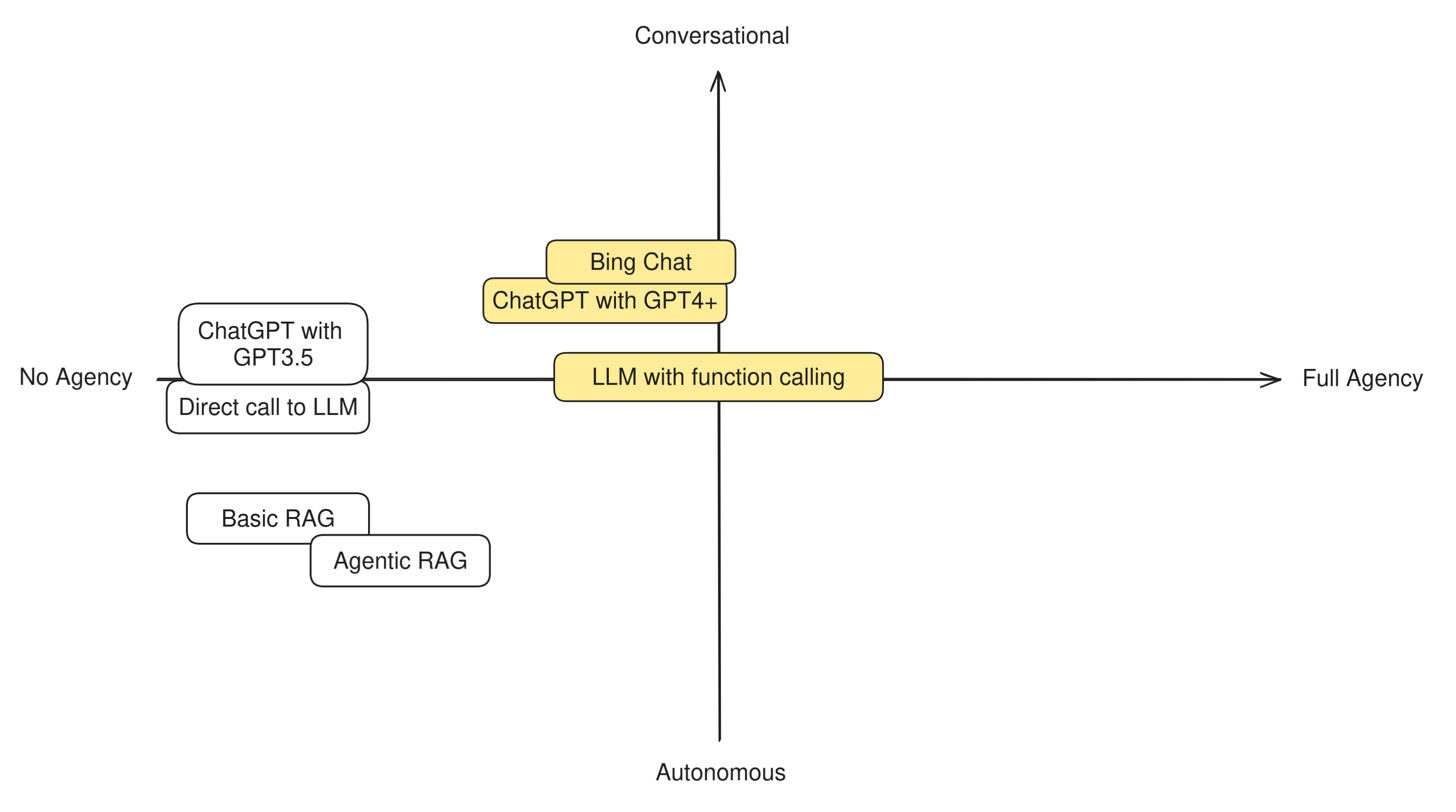

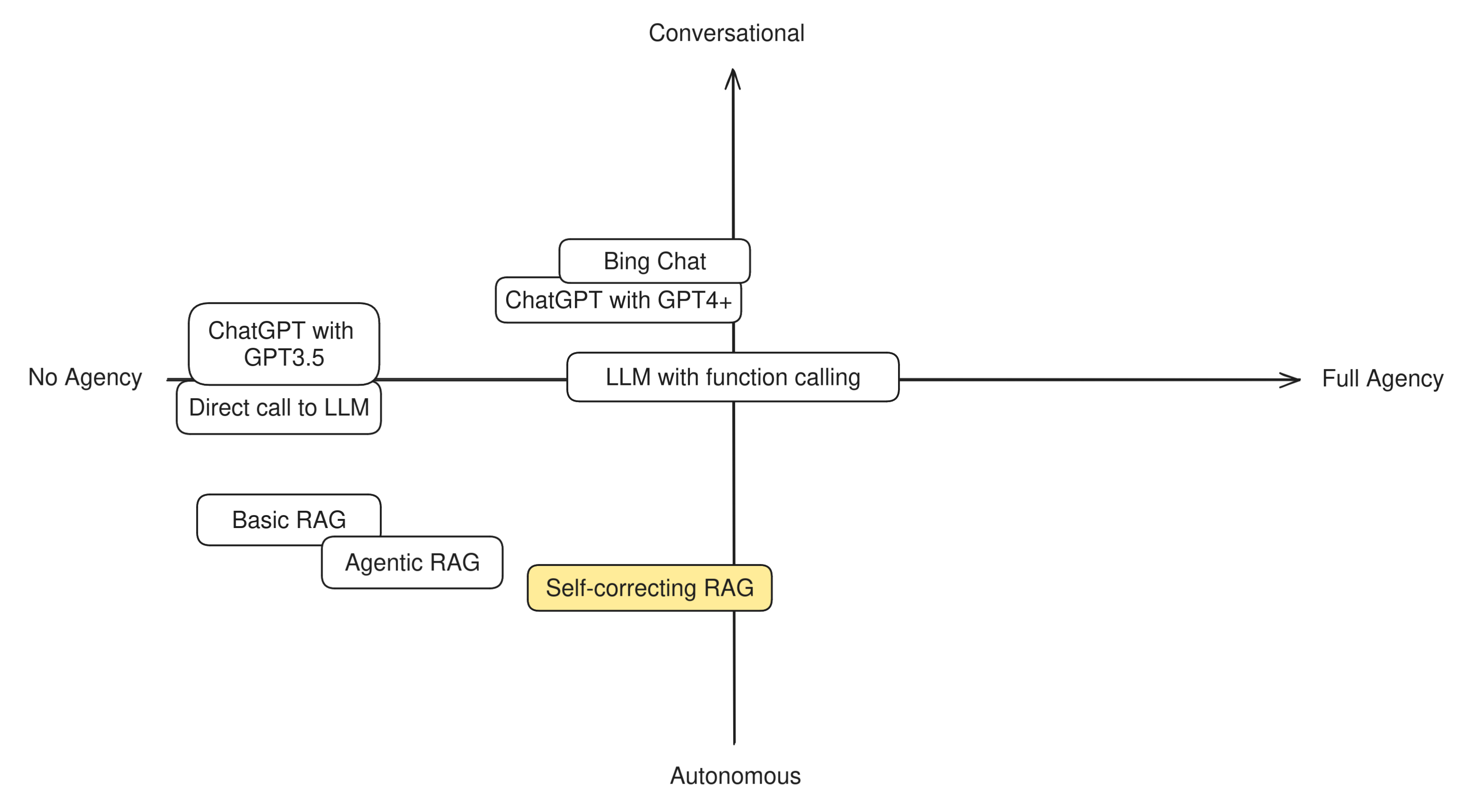

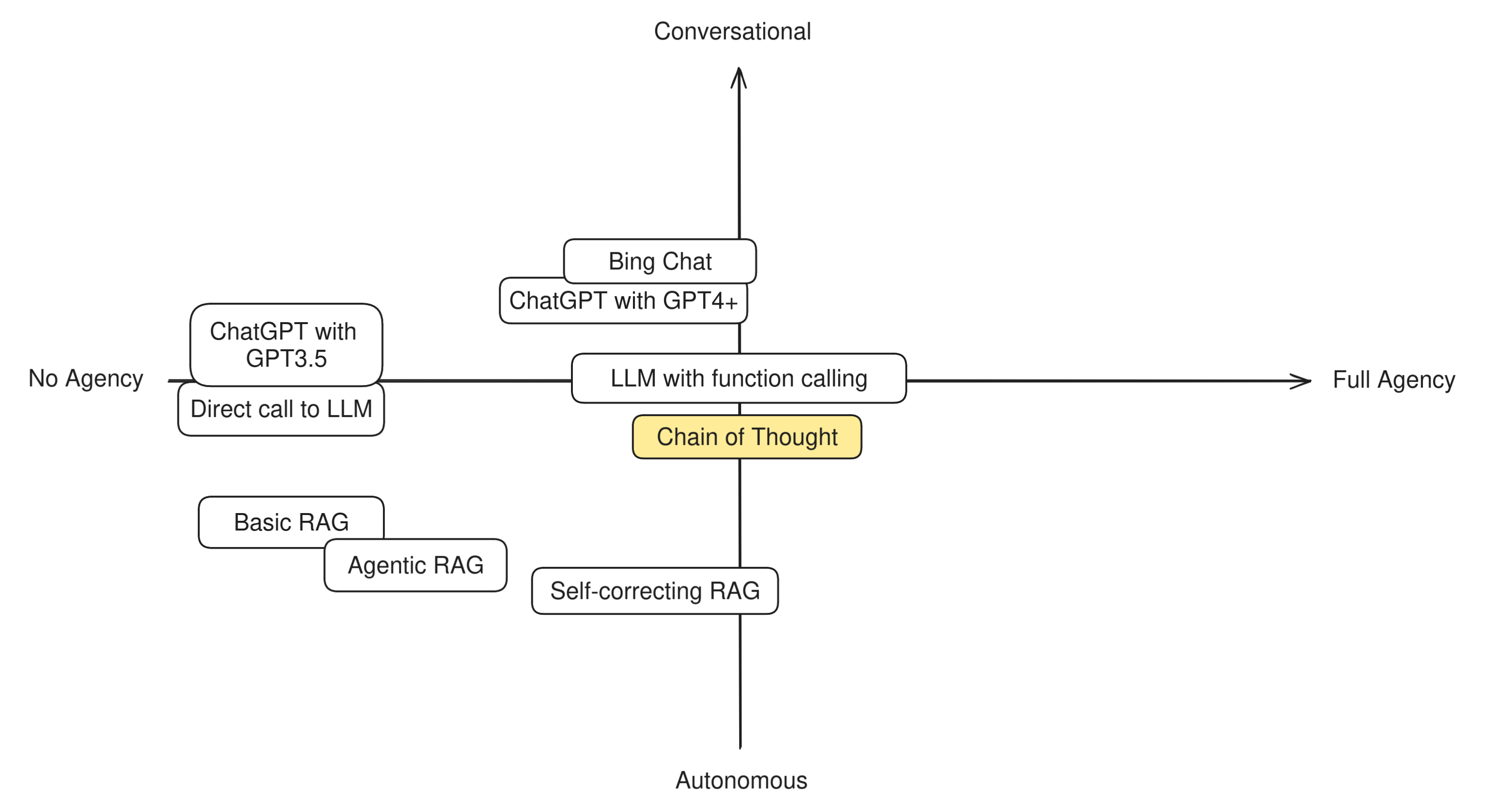

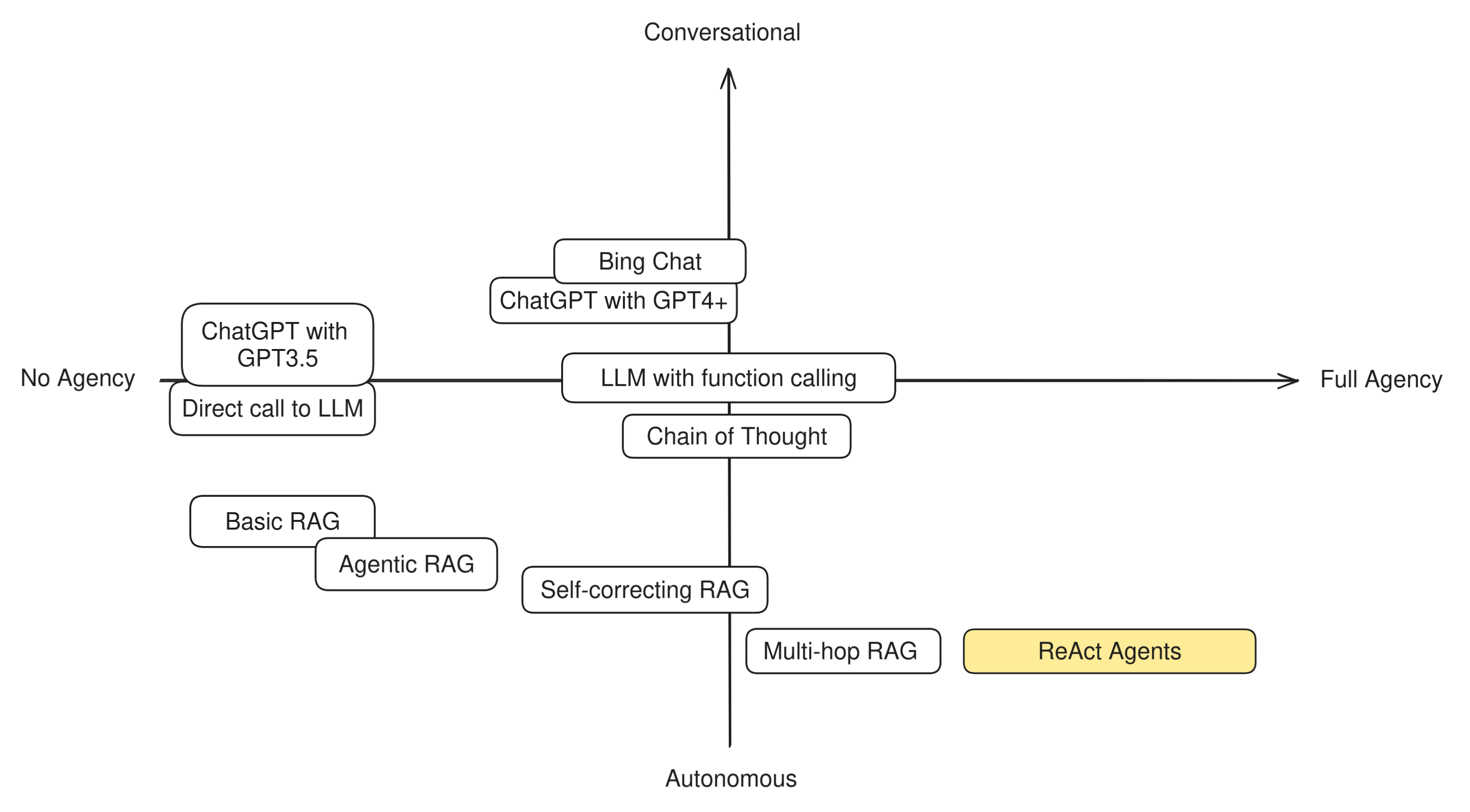

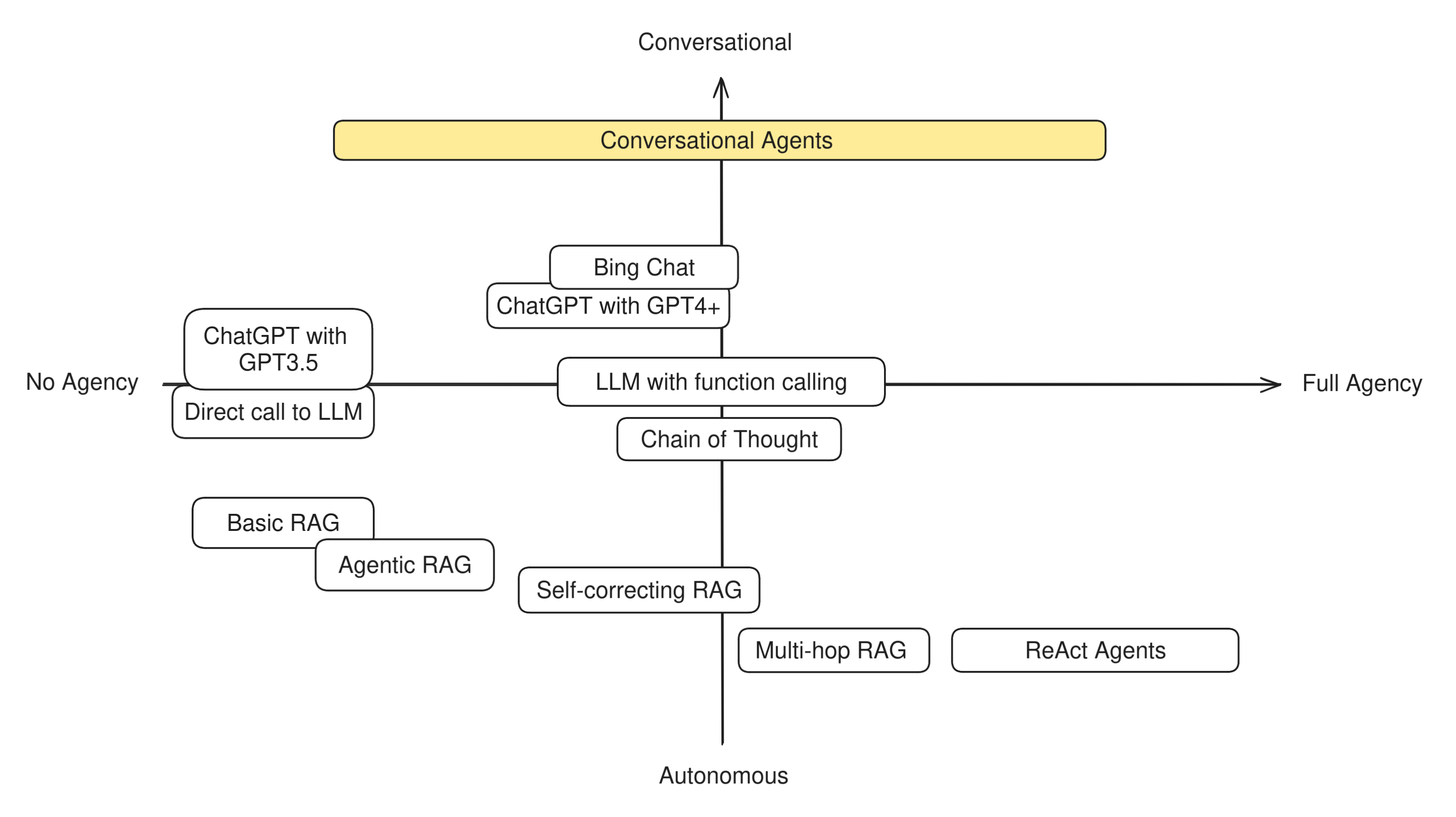

All the distinctions we made above are best understood as a continuous spectrum rather than hard categories. Various AI systems may have more or less agency and may be tuned towards a more “autonomous” or “conversational” behavior.

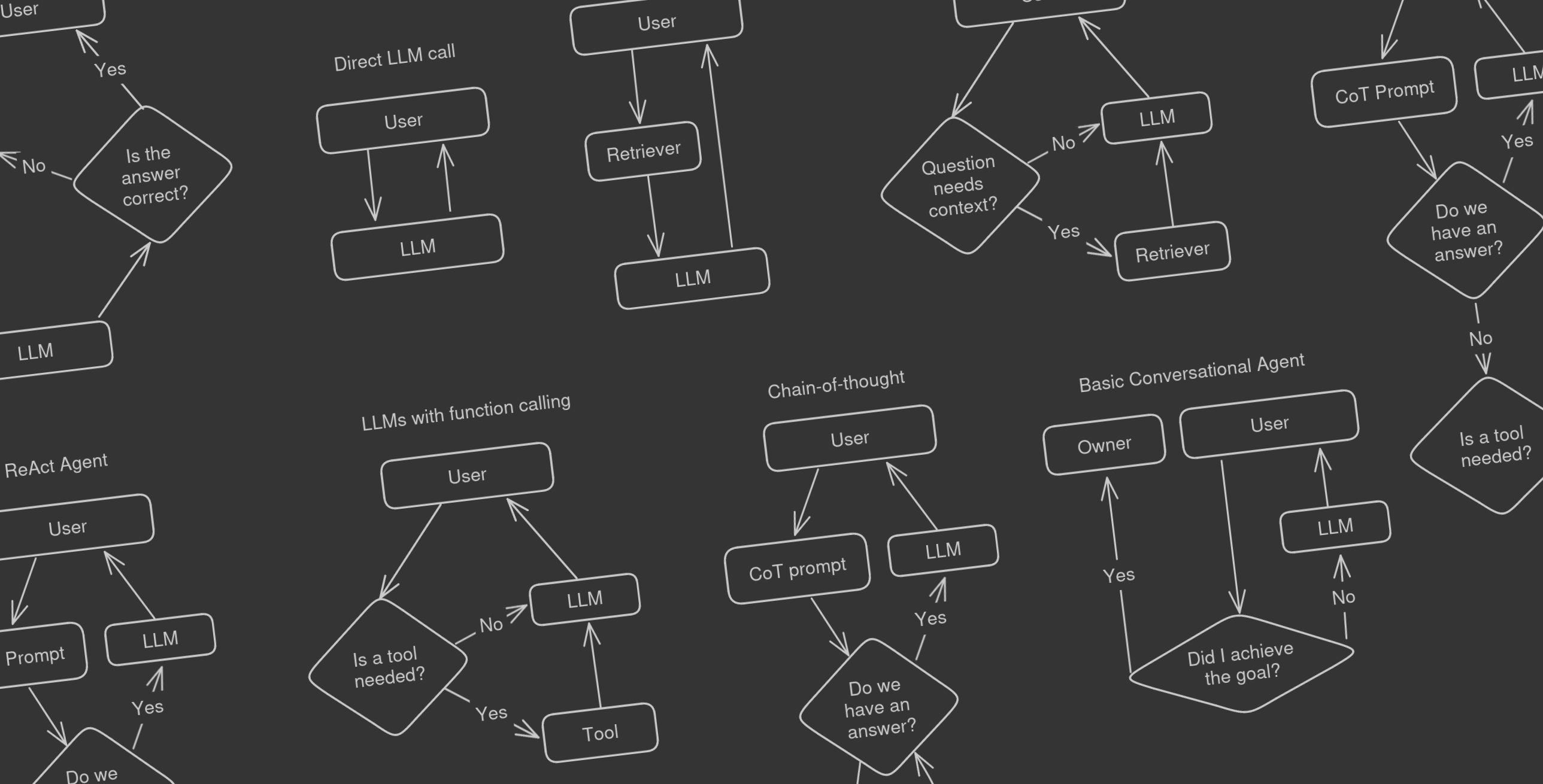

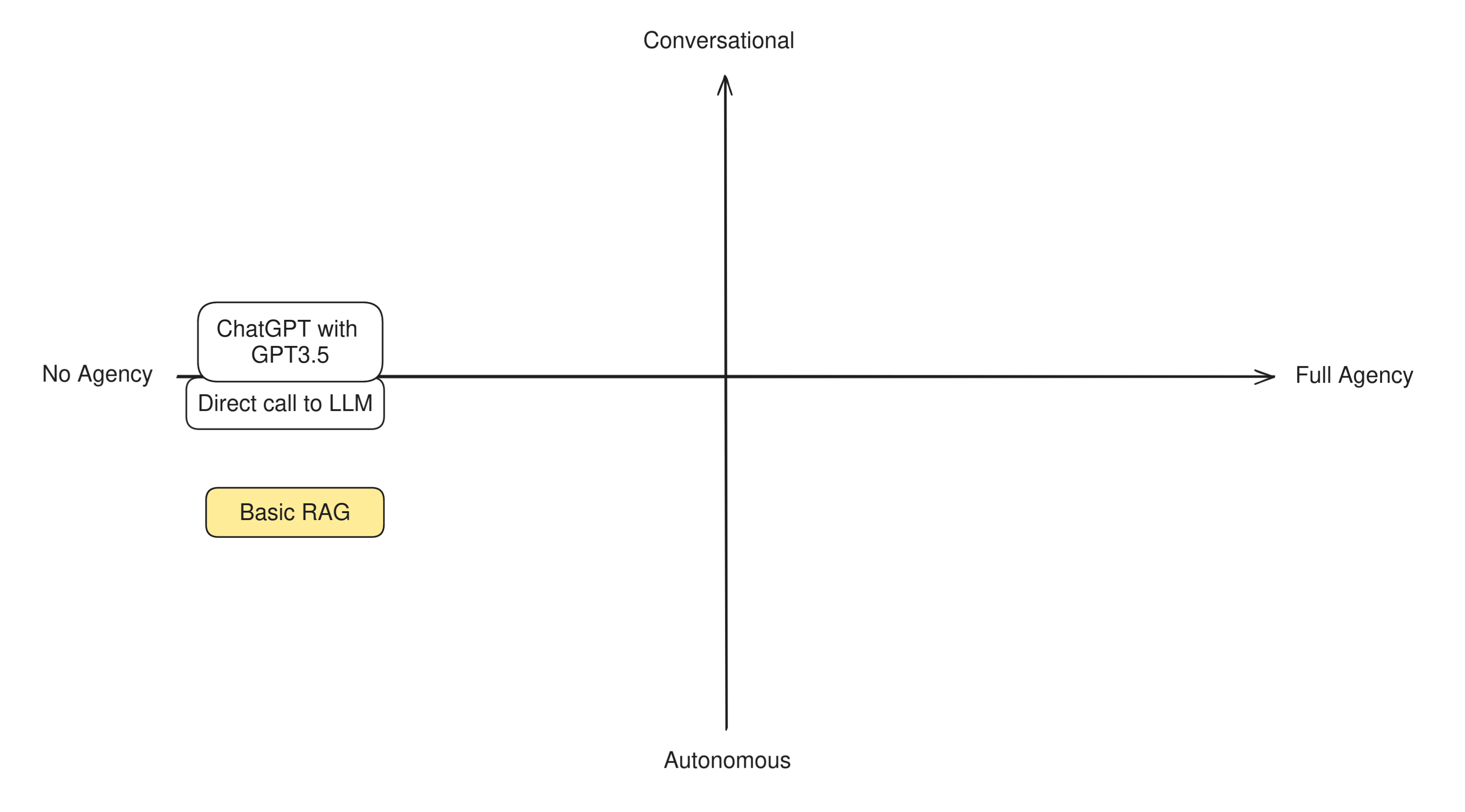

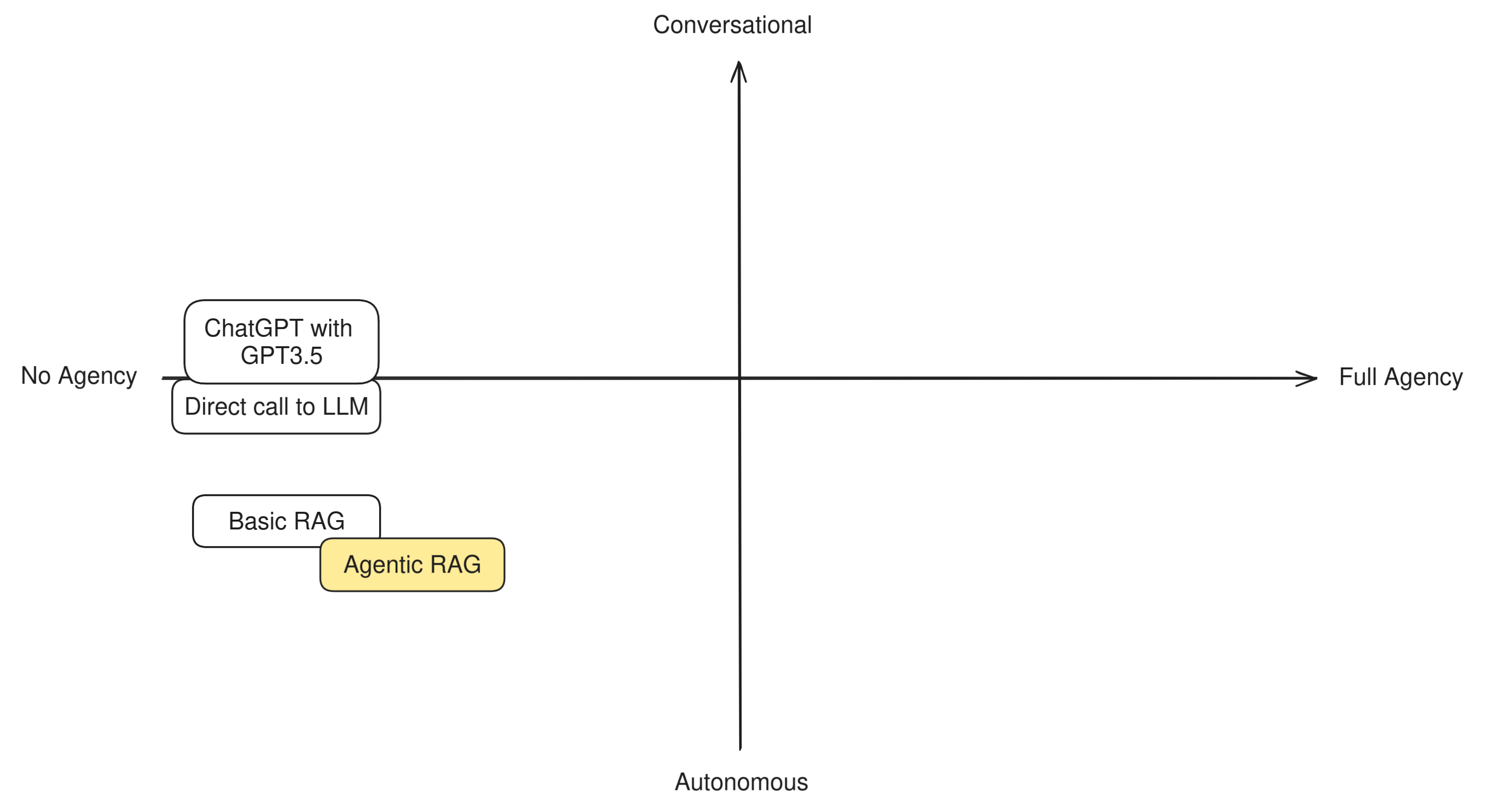

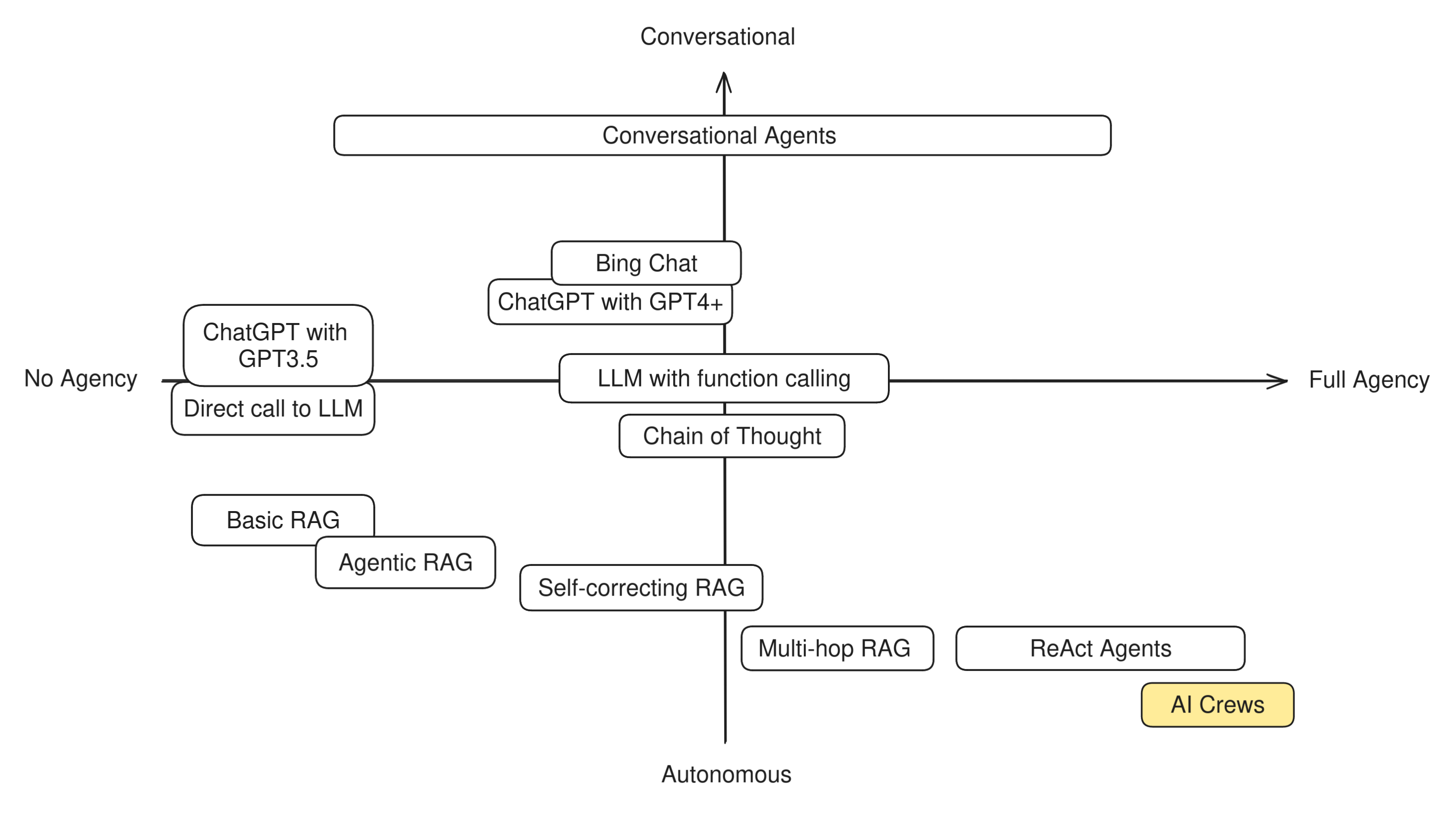

In order to understand this difference in practice, let’s try to categorize some well-known LLM techniques and apps to see how “agentic” they are. Having two axis to measure by, we can build a simple compass like this:

Bare LLMs

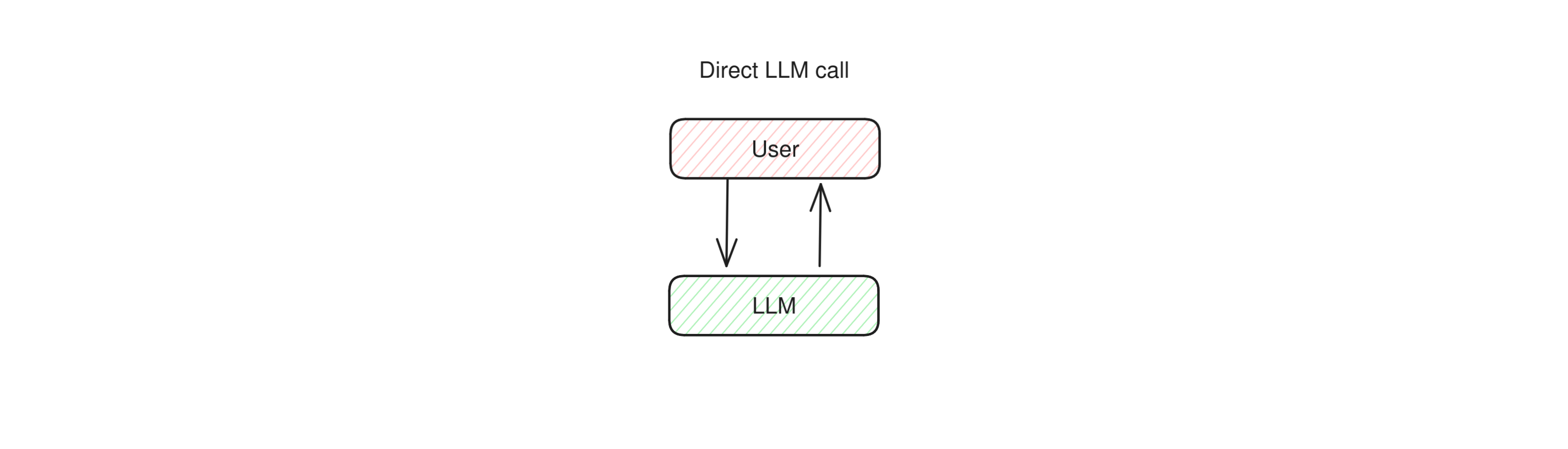

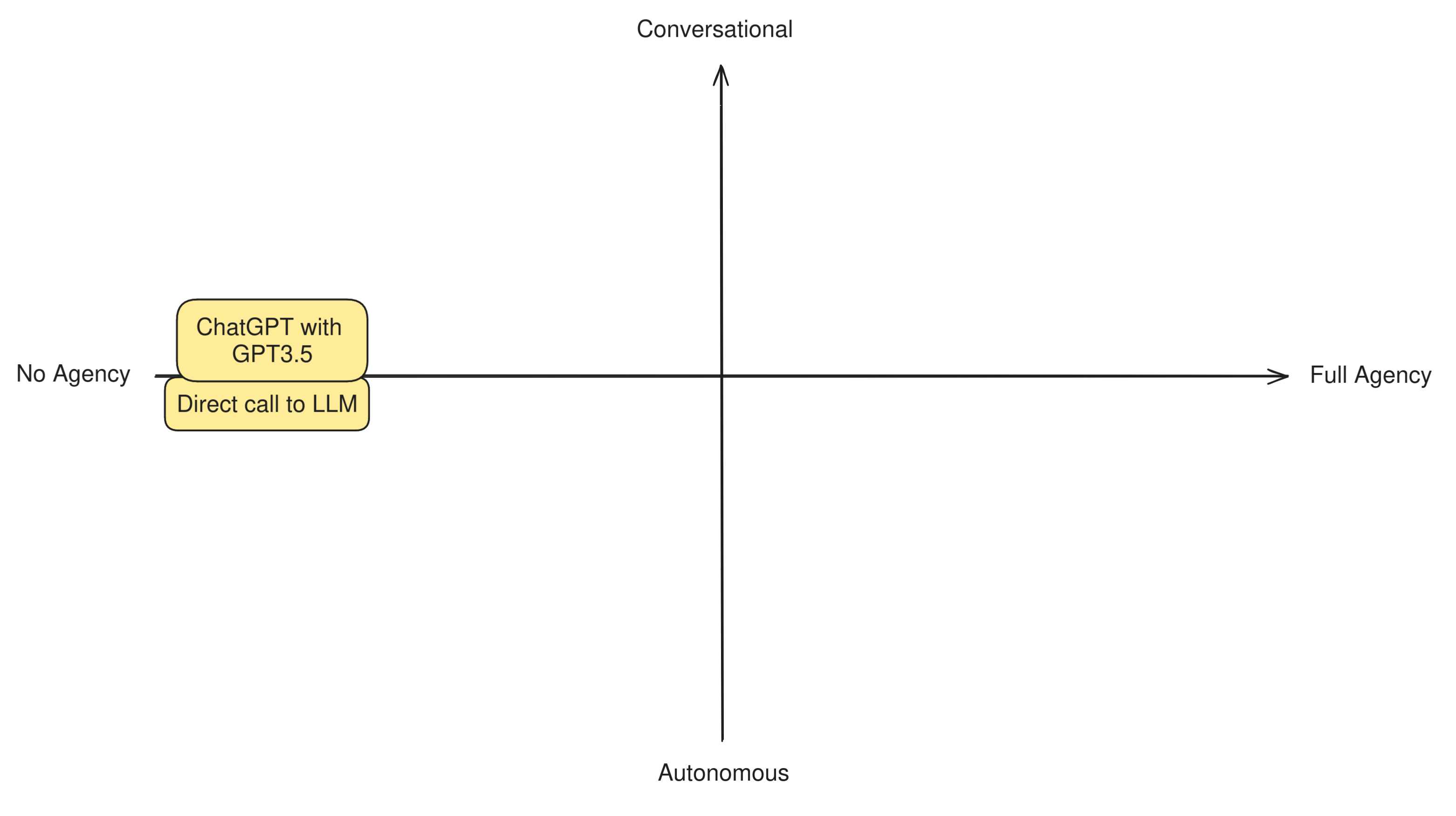

Many apps out there perform nothing more than direct calls to LLMs, such as ChatGPT’s free app and other similarly simple assistants and chatbots. There are no more components to this system other than the model itself and their mode of operation is very straightforward: a user asks a question to an LLM, and the LLM replies directly.

This systems are not designed with the intent of accomplishing a goal, and neither can take any actions on the user’s behalf. They focus on talking with a user in a reactive way and can do nothing else than talk back. An LLM on its own has no agency at all.

At this level it also makes very little sense to distinguish between autonomous or conversational agent behavior, because the entire app shows no degrees of autonomy. So we can place them at the very center-left of the diagram.

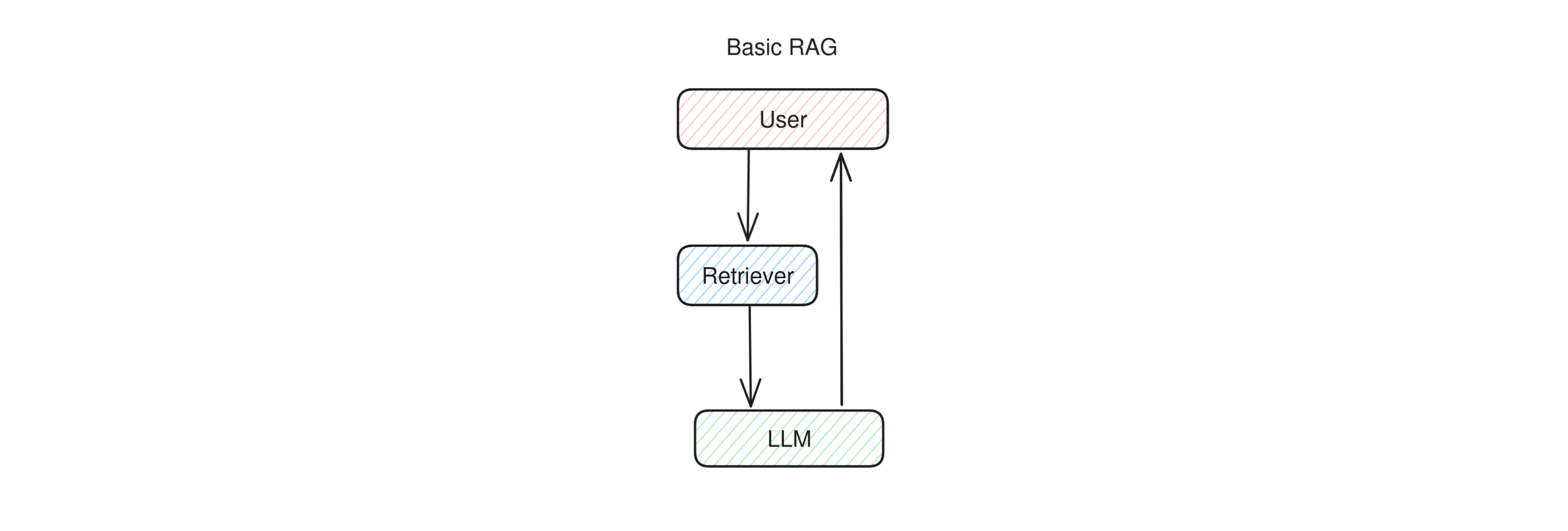

Basic RAG

Together with direct LLM calls and simple chatbots, basic RAG is also an example of an application that does not need any agency or goals to pursue in order to function. Simple RAG apps works in two stages: first the user question is sent to a retriever system, which fetches some additional data relevant to the question. Then, the question and the additional data is sent to the LLM to formulate an answer.

This means that simple RAG is not an agent: the LLM has no role in the retrieval step and simply reacts to the RAG prompt, doing little more than what a direct LLM call does. The LLM is given no agency, takes no decisions in order to accomplish its goals, and has no tools it can decide to use, or actions it can decide to take. It’s a fully pipelined, reactive system. However, we may rank basic RAG more on the autonomous side with respect to a direct LLM call, because there is one step that is done automonously (the retrieval).

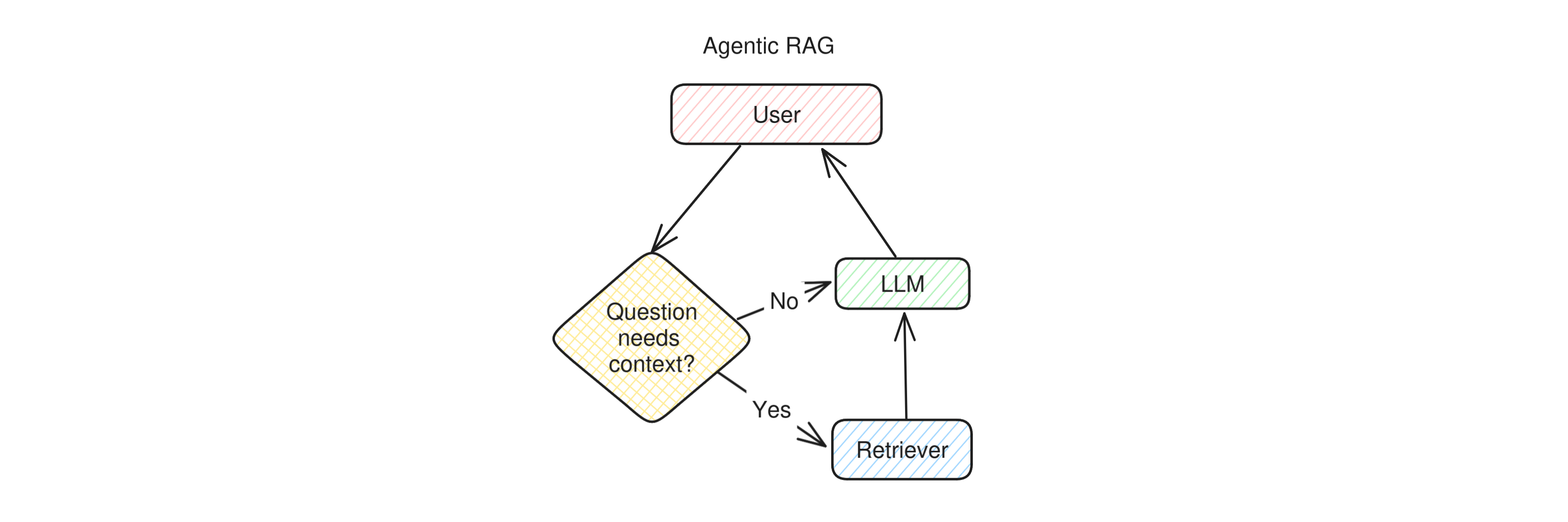

Agentic RAG

Agentic RAG is a slightly more advanced version of RAG that does not always perform the retrieval step. This helps the app produce better prompts for the LLM: for example, if the user is asking a question about trivia, retrieval is very important, while if they’re quizzing the LLM with some mathematical problem, retrieval might confuse the LLM by giving it examples of solutions to different puzzles, and therefore make hallucinations more likely.

This means that an agentic RAG app works as follows: when the user asks a question, before calling the retriever the app checks whether the retrieval step is necessary at all. Most of the time the preliminary check is done by an LLM as well, but in theory the same check coould be done by a properly trained classifier model. Once the check is done, if retrieval was necessary it is run, otherwise the app skips directly to the LLM, which then replies to the user.

You can see immediately that there’s a fundamental difference between this type of RAG and the basic pipelined form: the app needs to take a decision in order to accomplish the goal of answering the user. The goal is very limited (giving a correct answer to the user), and the decision very simple (use or not use a single tool), but this little bit of agency given to the LLM makes us place an application like this definitely more towards the Agent side of the diagram.

We keep Agentic RAG towards the Autonomous side because in the vast majority of cases the decision to invoke the retriever is kept hidden from the user.

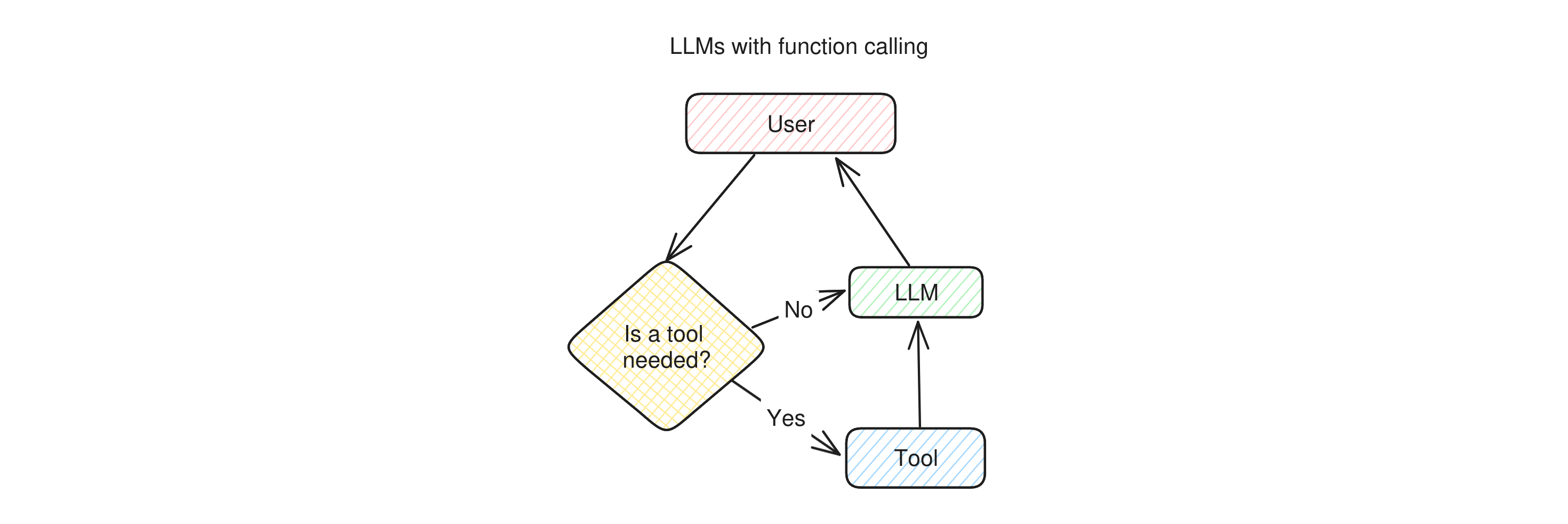

LLMs with function calling

Some LLM applications, such as ChatGPT with GPT4+ or Bing Chat, can make the LLM use some predefined tools: a web search, an image generator, and maybe a few more. The way they work is quite straightforward: when a user asks a question, the LLM first needs to decide whether it should use a tool to answer the question. If it decides that a tool is needed, it calls it, otherwise it skips directly to generating a reply, which is then sent back to the user.

You can see how this diagram resemble agentic RAG’s: before giving an answer to the user, the app needs to take a decision.

With respect to Agentic RAG this decision is a lot more complex: it’s not a simple yes/no decision, but it involves choosing which tool to use and also generate the input parameters for the selected tool that will provide the desired output. In many cases the tool’s output will be given to the LLM to be re-elaborated (such as the output of a web search), while in some other it can go directly to the user (like in the case of image generators). This all implies that more agency is given to the system and, therefore, it can be placed more clearly towards the Agent end of the scale.

We place LLMs with function calling in the middle between Conversational and Autonomous because the degree to which the user is aware of this decision can vary greatly between apps. For example, Bing Chat and ChatGPT normally notify the user that they’re going to use a tool when they do, and the user can instruct them to use them or not, so they’re slightly more conversational.

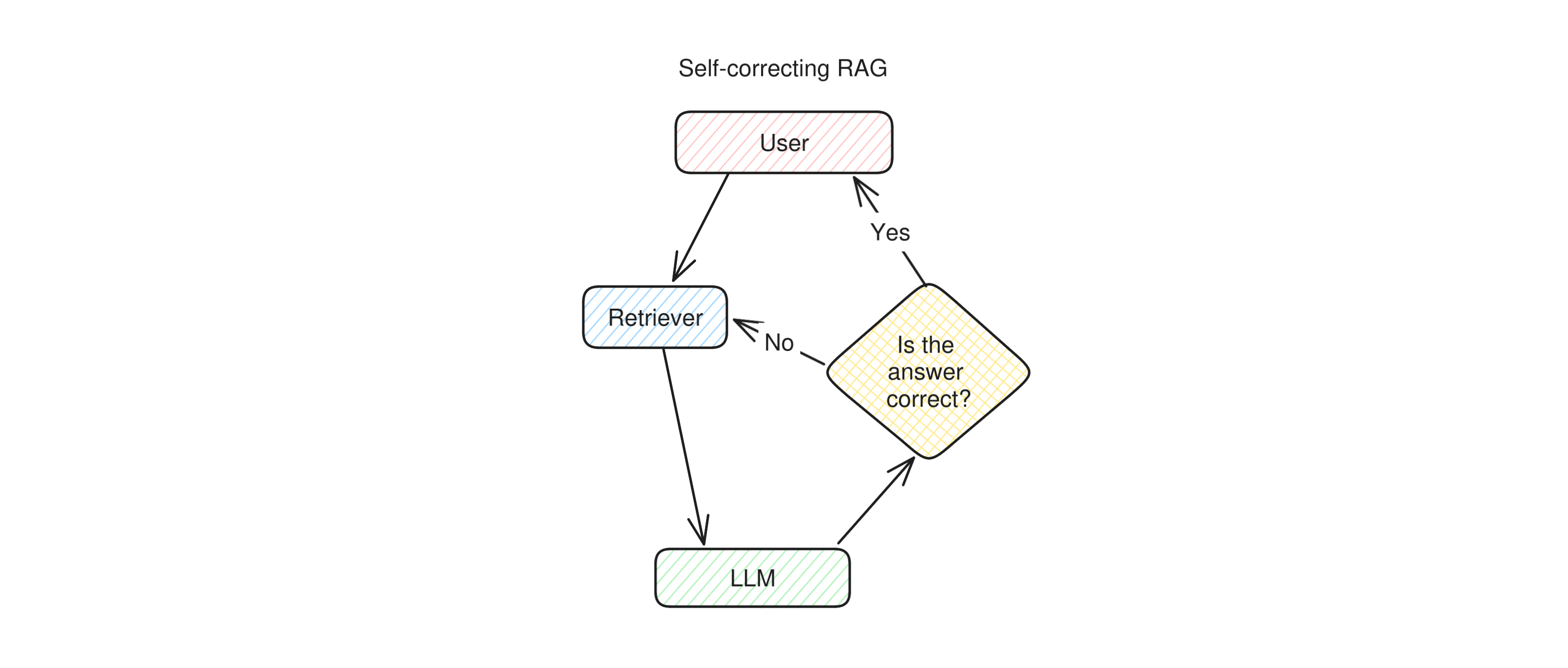

Self correcting RAG

Self-correcting RAG is a technique that improves on simple RAG by making the LLM double-check its replies before returning them to the user. It comes from an LLM evaluation technique called “LLM-as-a-judge”, because an LLM is used to judge the output of a different LLM or RAG pipeline.

Self-correcting RAG starts as simple RAG: when the user asks a question, the retriever is called and the results are sent to the LLM to extract an answer from. However, before returning the answer to the user, another LLM is asked to judge whether in their opinion, the answer is correct. If the second LLM agrees, the answer is sent to the user. If not, the second LLM generates a new question for the retriever and runs it again, or in other cases, it simply integrates its opinion in the prompt and runs the first LLM again.

Self-correcting RAG can be seen as one more step towards agentic behavior because it unlocks a new possibility for the application: the ability to try again. A self-correcting RAG app has a chance to detect its own mistakes and has the agency to decide that it’s better to try again, maybe with a slightly reworded question or different retrieval parameters, before answering the user. Given that this process is entirely autonomous, we’ll place this technique quite towards the Autonomous end of the scale.

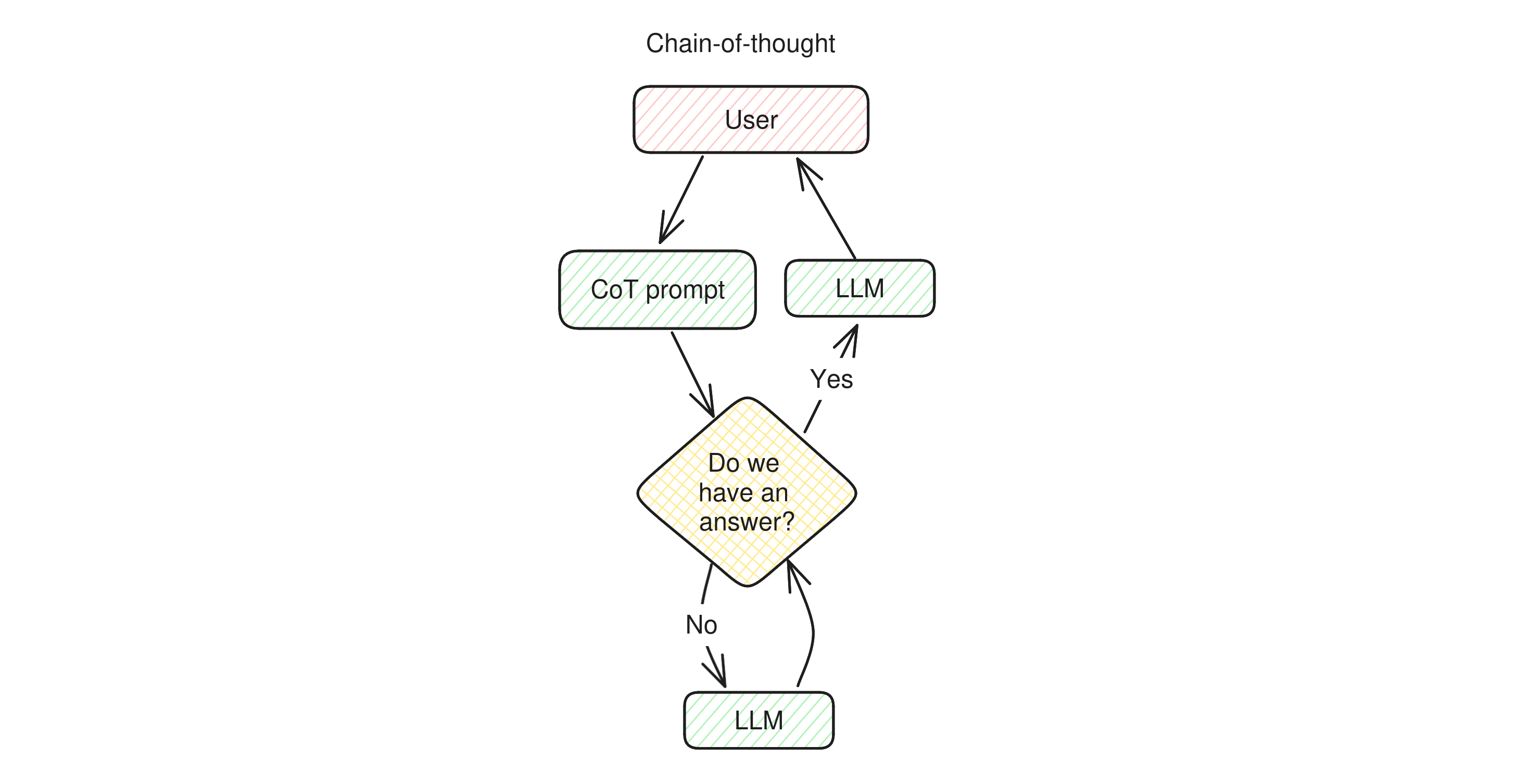

Chain-of-thought

Chain-of-thought is a family of prompting techniques that makes the LLM “reason out loud”. It’s very useful when the model needs to process a very complicated question, such as a mathematical problem or a layered question like “When was the eldest sistem of the current King of Sweden born?” Assuming that the LLM knows these facts, in order to not hallucinate it’s best to ask the model to proceed “step-by-step” and find out, in order:

- Who the current King of Sweden is,

- Whether he has an elder sister,

- If yes, who she is,

- The age of the person identified above.

The LLM might know the final fact in any case, but the probability of it giving the right answer increases noticeably if the LLM is prompted this way.

Chain-of-thought prompts can also be seen as the LLM accomplishing the task of finding the correct answer in steps, which implies that there are two lines of thinking going on: on one side the LLM is answering the questions it’s posing to itself, while on the other it’s constantly re-assessing whether it has a final answer for the user.

In the example above, the chain of thought might end at step 2 if the LLM realizes that the current King of Sweden has no elder sisters (he doesn’t): the LLM needs to keep an eye of its own thought process and decide whether it needs to continue or not.

We can summarize an app using chain-of-thought prompting like this: when a user asks a question, first of all the LLM reacts to the chain-of-thought prompt to lay out the sub-questions it needs to answer. Then it answers its own questions one by one, asking itself each time whether the final answer has already been found. When the LLM believes it has the final answer, it rewrites it for the user and returns it.

This new prompting technique makes a big step towards full agency: the ability for the LLM to assess whether the goal has been achieved before returning any answer to the user. While apps like Bing Chat iterate with the user and need their feedback to reach high-level goals, chain-of-thought gives the LLM the freedom to check its own answers before having the user judge them, which makes the loop much faster and can increase the output quality dramatically.

This process is similar to what self-correcting RAG does, but has a wider scope, because the LLM does not only need to decide whether an answer is correct, it can also decide to continue reasoning in order to make it more complete, more detailed, to phrase it better, and so on.

Another interesting trait of chain-of-thought apps is that they introduce the concept of inner monologue. The inner monologue is a conversation that the LLM has with itself, a conversation buffer where it keeps adding messages as the reasoning develops. This monologue is not visible to the user, but helps the LLM deconstruct a complex reasoning line into a more manageable format, like a researcher that takes notes instead of keeping all their earlier reasoning inside their head all the times.

Due to the wider scope of the decision-making that chain-of-thought apps are able to do, they also place in the middle of our compass They can be seen as slightly more autonomous than conversational due to the fact that they hide their internal monologue to the user.

From here, the next step is straightforward: using tools.

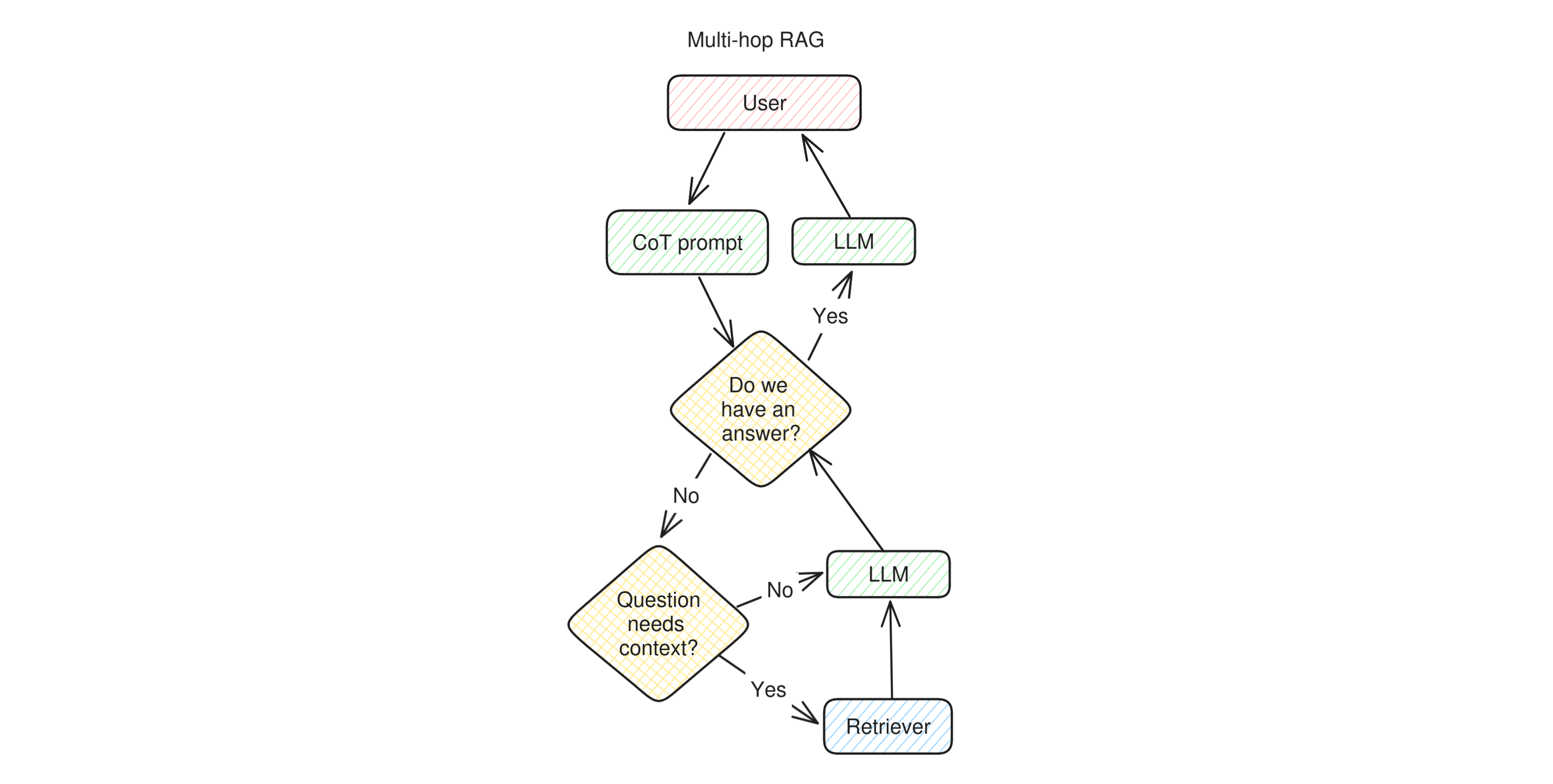

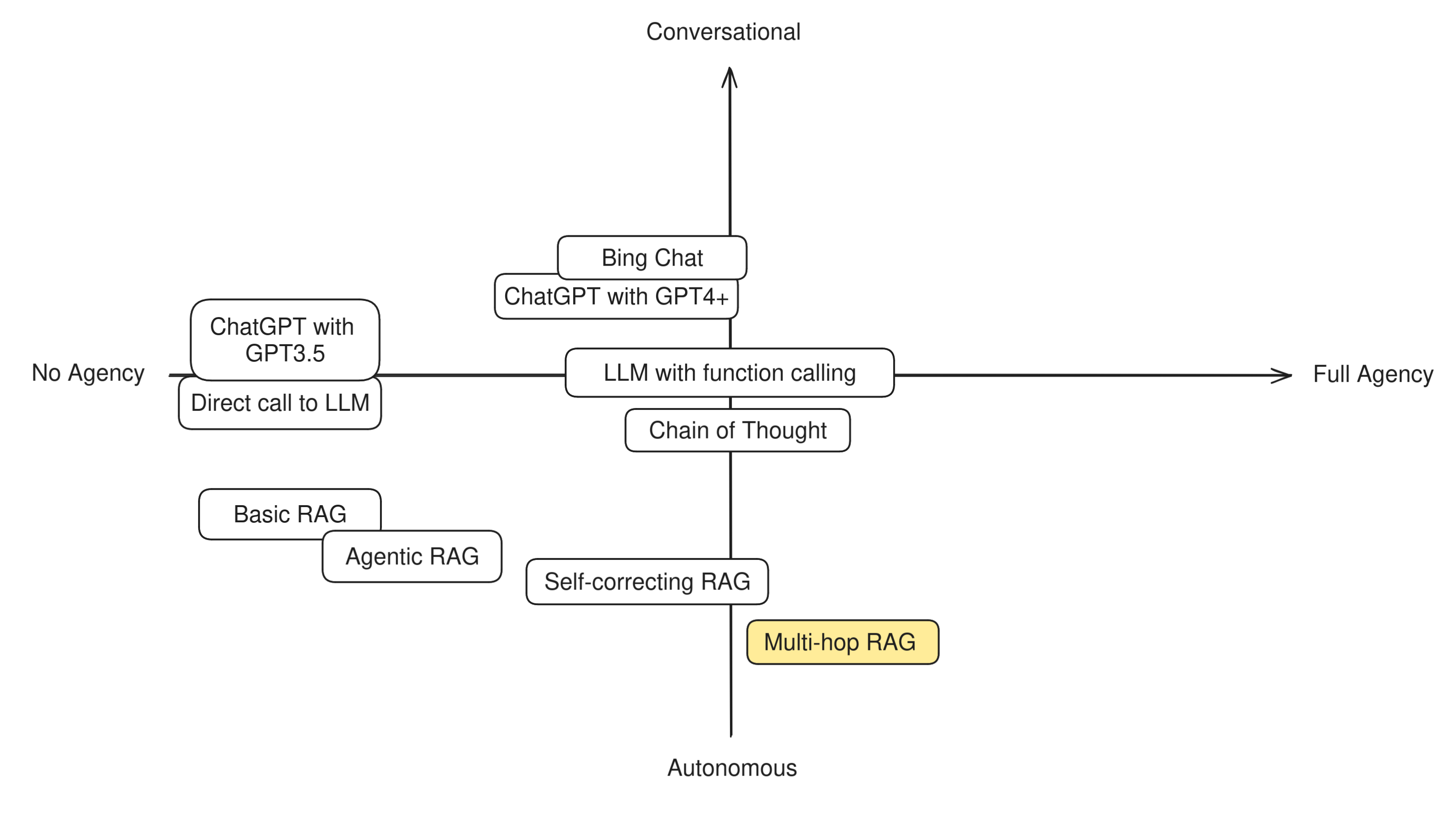

Multi-hop RAG

Multi-hop RAG applications are nothing else than simple RAG apps that use chain-of-thought prompting and are free to invoke the retriever as many times as needed and only when needed.

This is how it works. When the user makes a question, a chain of thought prompt is generated and sent to the LLM. The LLM assesses whether it knows the answer to the question and if not, asks itself whether a retrieval is necessary. If it decides that retrieval is necessary it calls it, otherwise it skips it and generates an answer directly. It then checks again whether the question is answered. Exiting the loop, the LLM produces a complete answer by re-reading its own inner monologue and returns this reply to the user.

An app like this is getting quite close to a proper autonomous agent, because it can perform its own research autonomously. The LLM calls are made in such a way that the system is able to assess whether it knows enough to answer or whether it should do more research by formulating more questions for the retriever and then reasoning over the new collected data.

Multi-hop RAG is a very powerful technique that shows a lot of agency and autonomy, and therefore can be placed in the lower-right quadrant of out compass. However, it is still limited with respect to a “true” autonomous agent, because the only action it can take is to invoke the retriever.

ReAct Agents

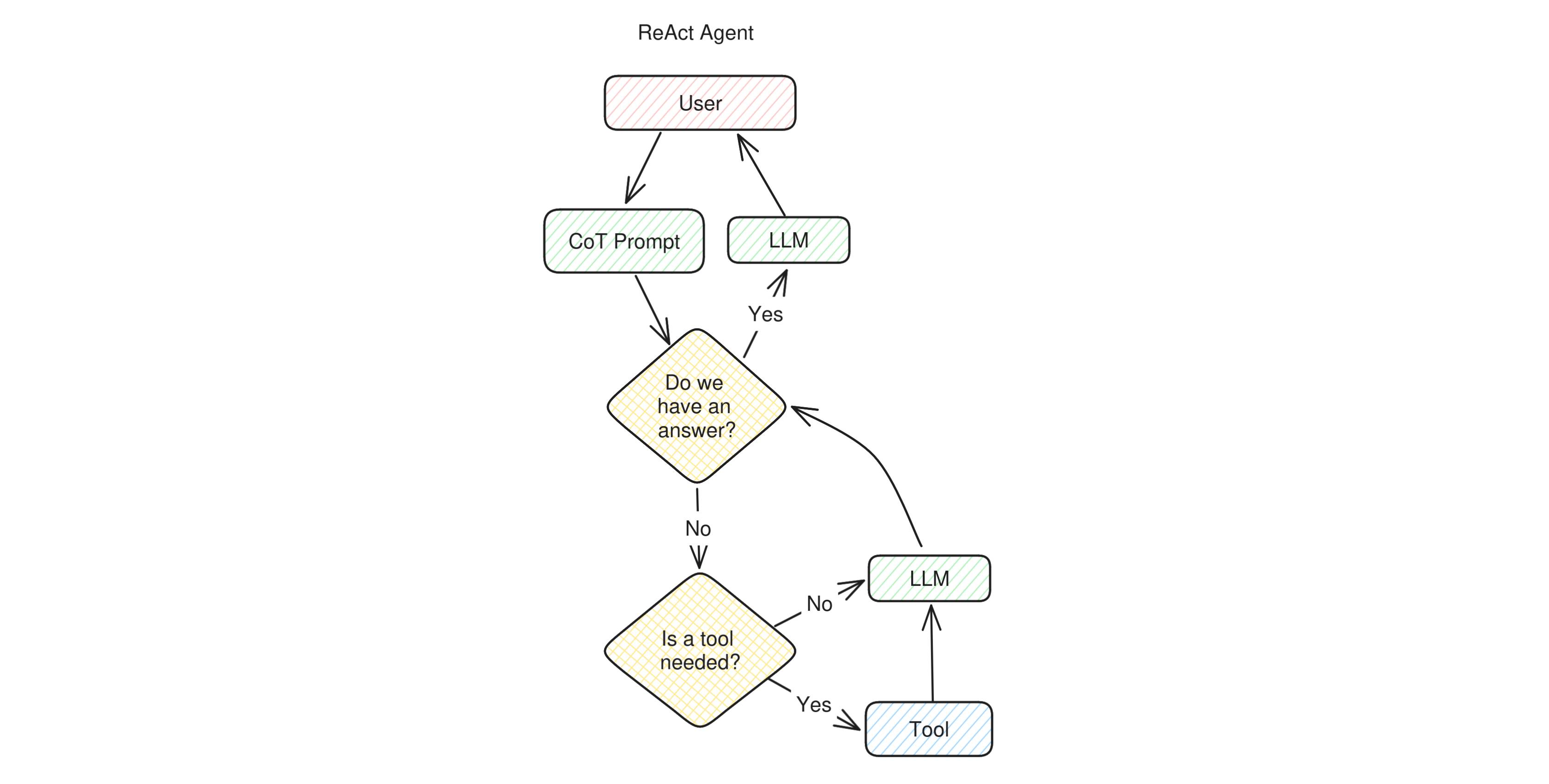

Let’s now move onto apps that can be defined proper “agents”. One of the first flavor of agentic LLM apps, and still the most popular nowadays, is called “ReAct” Agents, which stands for “Reason + Act”. ReAct is a prompting technique that belongs to the chain-of-thought extended family: it makes the LLM reason step by step, decide whether to perform any action, and then observe the result of the actions it took before moving further.

A ReAct agent works more or less like this: when user sets a goal, the app builds a ReAct prompt, which first of all asks the LLM whether the answer is already known. If the LLM says no, the prompt makes it select a tool. The tool returns some values which are added to the inner monologue of the application toghether with the invitation to re-assess whether the goal has been accomplished. The app loops over until the answer is found, and then the answer is returned to the user.

As you can see, the structure is very similar to a multi-hop RAG, with an important difference: ReAct Agents normally have many tools to choose from rather than a single retriever. This gives them the agency to take much more complex decisions and can be finally called “agents”.

ReAct Agents are very autonomous in their tasks and rely on an inner monologue rather than a conversation with a user to achieve their goals. Therefore we place them very much on the Autonomous end of the spectrum.

Conversational Agents

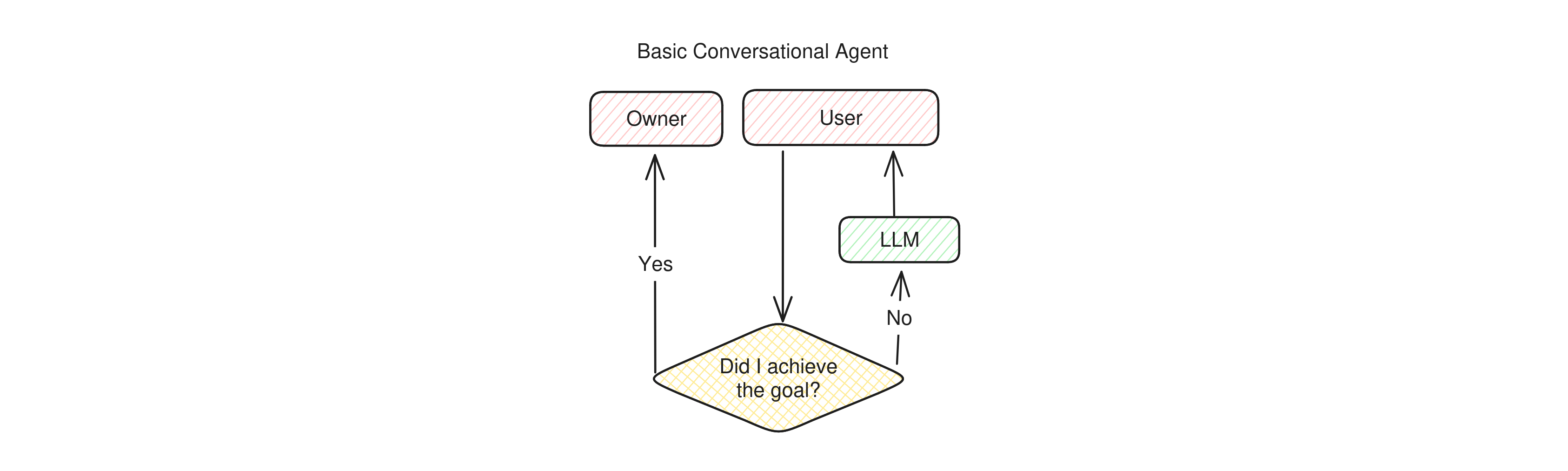

Conversational Agents are a category of apps that can vary widely. As stated earlier, conversational agents focus on using the conversation itself as a tool to accomplish goals, so in order to understand them, one has to distinguish between the people that set the goal (let’s call them owners) and those who talk with the bot (the users).

Once this distinction is made, this is how the most basic conversational agents normally work. First, the owner sets a goal. The application then starts a conversation with a user and, right after the first message, starts asking itself if the given goal was accomplished. It then keeps talking to the target user until it believes the goal was attained and, once done, it returns back to its owner to report the outcome.

Basic conversational agents are very agentic in the sense that they can take a task off the hands of their owners and keep working on them until the goal is achieved. However, they have varying degrees of agency depending on how many tools they can use and how sophisticated is their ability to talk to their target users.

For example, can the communication occurr over one single channel, be it email, chat, voice, or something else? Can the agent choose among different channels to reach the user? Can it perform side tasks to behalf of either party to work towards its task? There is a large variety of these agents available and no clear naming distinction between them, so depending on their abilities, their position on our compass might be very different. This is why we place them in the top center, spreading far out in both directions.

AI Crews

By far the most advanced agent implementation available right now is called AI Crew, such as the ones provided by CrewAI. These apps take the concept of autonomous agent to the next level by making several different agents work together.

The way these apps works is very flexible. For example, let’s imagine we are making an AI application that can build a fully working mobile game from a simple description. This is an extremely complex task that, in real life, requires several developers. To achieve the same with an AI Crew, the crew needs to contain several agents, each one with their own special skills, tools, and background knowledge. There could be:

- a Designer Agent, that has all the tools to generate artwork and assets;

- a Writer Agent that writes the story, the copy, the dialogues, and most of the text;

- a Frontend Developer Agent that designs and implements the user interface;

- a Game Developer Agent that writes the code for the game itself;

- a Manager Agent, that coordinates the work of all the other agents, keeps them on track and eventually reports the results of their work to the user.

These agents interact with each other just like a team of humans would: by exchanging messages in a chat format, asking each other to perform actions for them, until their manager decides that the overall goal they were set to has been accomplished, and reports to the user.

AI Crews are very advanced and dynamic systems that are still actively researched and explored. One thing that’s clear though is that they show the highest level of agency of any other LLM-based app, so we can place them right at the very bottom-right end of the scale.

Conclusion

What we’ve seen here are just a few examples of LLM-powered applications and how close or far they are to the concept of a “real” AI agent. AI agents are still a very active area of research, and their effectiveness is getting more and more reasonable as LLMs become cheaper and more powerful.

As matter of fact, with today’s LLMs true AI agents are possible, but in many cases they’re too brittle and expensive for real production use cases. Agentic systems today suffer from two main issues: they perform huge and frequent LLM calls and they tolerate a very low error rate in their decision making.

Inner monologues can grow to an unbounded size during the agent’s operation, making the context window size a potential limitation. A single bad decision can send a chain-of-thought reasoning train in a completely wrong direction and many LLM calls will be performed before the system realizes its mistake, if it does at all. However, as LLMs become faster, cheaper and smarter, the day when AI Agent will become reliable and cheap enough is nearer than many think.

Let’s be ready for it!